by Paul R. Spitzzeri

In its important study on the early history and development of the City of Industry as a basis for future planning, Stanford Research Institute’s 1970 report looked at fiscal policies and practices from incorporation in June 1957 through mid-year 1963 noting that a local sales and use tax of 1% was the city’s main source of revenue, about 80% on average, allowing it “to avoid imposition of a property tax.”

The remainder of city income came from permits, licenses and franchises, with half of these generated from construction permit fees with the idea of covering fees from the county for inspections and other services so that net revenue there was essentially nothing. Another revenue stream was from interest earned on revenue surplus in bank accounts.

Restricted fund revenues primarily came from motor vehicle fines and forfeitures, with those monies going to a Traffic Safety Fund for street sweeping, striping, signage, signals and much of the maintenance of roads. These dollars constituted the second largest source of revenue outside of sales taxes for the city.

Small amounts came from the state and county through gas tax funds apportioned by population, so the city received little money from both entities. Naturally, these funds were also directed to the maintenance of streets. The report noted, however, that dollars from government, including the federal level, did benefit the city on a general level, including for freeways, flood control projects, and master plans for county roads.

When it came to disbursements, the report observed that “a large portion of the City’s receipts have been unspent,” totaling some $800,000 in the six-year period. Much of this was due to the fact that a lower percentage, about a third, of total revenues than was typical was devoted to general administration expenses, primarily to engineering services, insurance and council salaries (these latter, however, only began with the 1962-63 fiscal year.)

Funds dedicated to streets and roads constituted the second largest category of city spending and amounted to a little under 20% of revenues. Notably, only $17,000 was for new streets with nearly $400,000 going to maintenance. Other major areas included public safety, about 60% of this going towards contracted law enforcement services through the county sheriff’s department and other funds going towards building and safety inspections conducted by the county planning department; and capital spending for land, buildings, furnishings and other expenses, totaling about $280,000.

That hefty net balance of $800,000 led the authors to conclude that “if there were a larger administrative staff for the City, including a finance director, it is possible that these funds might be invested more advantageously” and suggested, at any rate, that bank deposited funds be placed in money market accounts offering higher yields (definitely a strategy that would not apply today!)

In a portion dealing with transportation, it was stated that the city’s unusual narrow, serpentine shape meant more linear miles of streets were needed. Moreover, realtors and business owners “find the layout of streets less than ideal.” At the time, the only west-east road that served well for heavy truck transport was Valley Boulevard. Gale Avenue, south of Valley, did not provide that level of service. The constructon of the Pomona Freeway, however, was underway and expected to be finished through the city by 1970 and provide better service.

By contrast, there were many north-south streets, but these were not generally suited to heavy truck use. Hacienda Boulevard, for example, which is just east of the Homestead, had potential for improvement within the city, but the narrowness of Industry limited the effectiveness of this especially as Hacienda went to a two-lane road south over the Puente Hills and then went into residential areas to the north (or did, until commercial zoning changed.)

There was, though, what was then Anaheim-Puente Road, now Azusa Avenue, and it was considered “the only north-south road in an area of considerable industrial expansion.” At the time, however, “the inadequacy of this road to handle traffic . . . is admitted by all concerned.” Disagreement about what to do to remediate the problem existed among the interested parties, including the city, county, state and the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, whose grade crossings were (and remain) a major issue. Eventually, there was widening, rerouting and a major overpass built across the Southern Pacific track and Valley Boulevard for the new Azusa Avenue.

While there are other major roadways east of Azusa, these being Fullerton Road, Nogales Street, Lemon Avenue and Fairway Avenue, the report skipped over to “La Brea Canyon Road,” really Brea Canyon Road, but this wound up being reconstituted as the 57 Freeway for most of the route, with a section branching northwest to Valley Boulevard in future work.

In 1964, however, most improvements were several years away and current conditions for truck traffic through the city were problematic, in terms of time, cost, competition for many businesses. An interesting matter was the “dray zone,” a distance from downtown Los Angeles to which free pick-up and delivery services were usual, though there was talk of an expansion of the zone to Nogales Street in 1964. There was also discussion of the matter of shipping costs to Industry from the downtown Los Angeles manufacturing district–yet future evolutions in both manufacturing zones and the nature of manufacturing in the United States generally were not considered.

With regard to shipping and freeways, it was noted that Interstate 10 was congested, about a decade after completion, and this affected the city, so it was hoped that future improvements including the building of the Pomona, San Gabriel River Freeway, and Brea Canyon (Orange) freeways were anticipated to make major changes to access of large vehicles to the city.

Yet, the importance of the two railroad lines was also stated for those businesses which manufactured and shipped in large enough quantities to fill carloads (rather than truckloads) of material. The connection of these lines, as well as freeways, to the port facilities of Los Angeles and Long Beach was also discussed, again primarily with those businesses in Industry that produced large quantities of goods. Though Ontario International Airport was fifteen miles from the east end of the city and Los Angeles International Airport thirty miles from the west end, most business leaders indicated that proximity to these facilities was not a major factor in their operations.

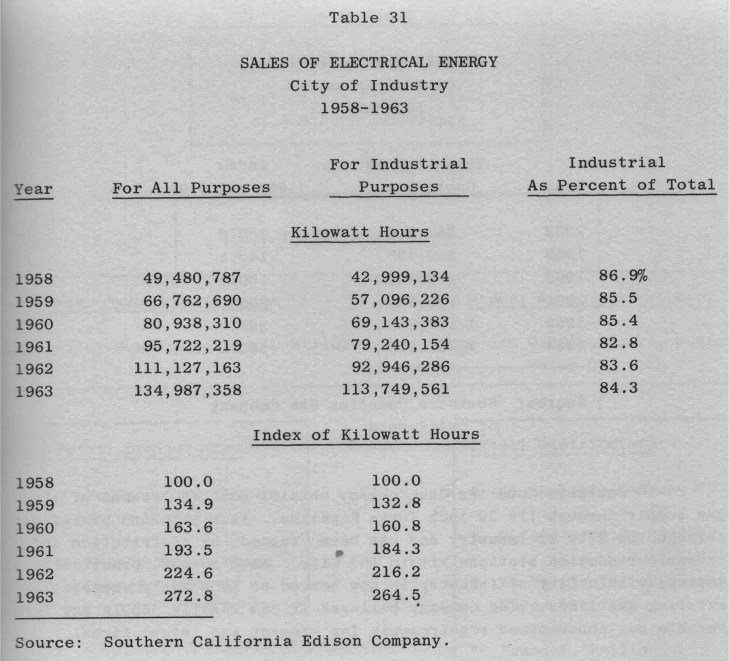

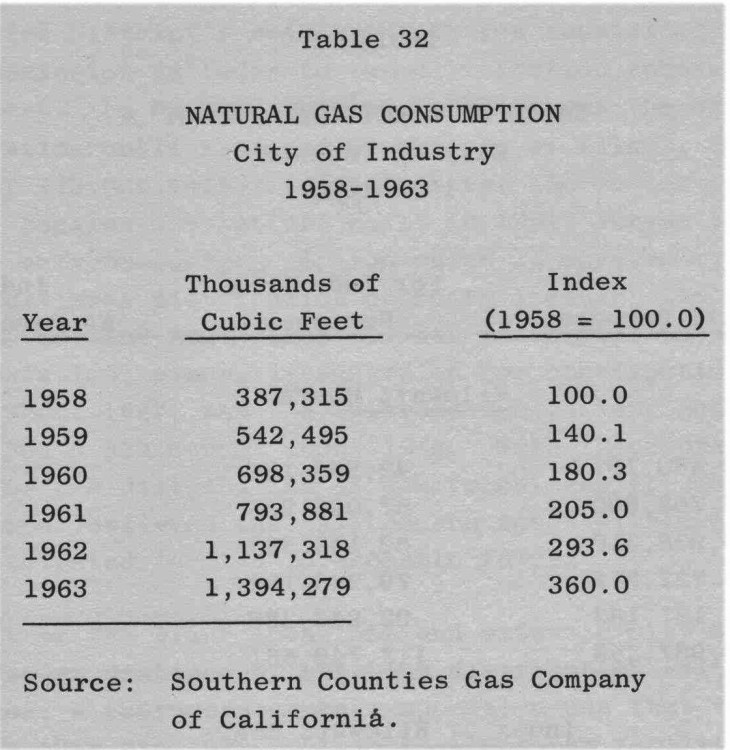

A section on utilities includes the discussion of electricity and the fact that new substations were being planned and built, especially given that the dramatic growth of the previous several years was manifested in a table showing a near tripling of sales of electricity, of which about 84% of that went to industrial uses. Similarly, gas consumption in terms of cubic feet leapt from under 400,000 to nearly 1.4 millon in six years and the main line from Southern California Gas travels through city making “tapping” into the line easy for local businesses.

Water supply is always a crucial issue in our region and the discussion in the report talked extensively about future supplies and the provision of future needs for the city. What was referred to as the Feather River Project, now known as the State Water Project, was particularly mentioned and the 1972 estimate proved to be reasonable, as the first supplies to southern California through the SWP arrived the following year. Extensive discussion and tables concerned water rates provided through the several companies selling water retail.

Telephone service, sanitary sewer systems, and storm and flood control areas were also covered, as was air pollution, but this latter section was relatively brief, with the report’s authors noting “City of Industry will record higher concentrations of air pollution despite its minimum contributions to that pollution,” though they don’t offer evidence as to how they arrived at the conclusion of “minimum contributions,” especially for a city that was so heavily involved in manufacturing. Still, it was recommended that “any industrial firm planning to locate in City of Industry would be well advised to utilize the gratuitous (meaning free, not unjustified!) guidance offered through” the local pollution control district.

Next week, we’ll look at sections dealing with industrial land use, inventory, prices and other related issues.