by Paul R. Spitzzeri

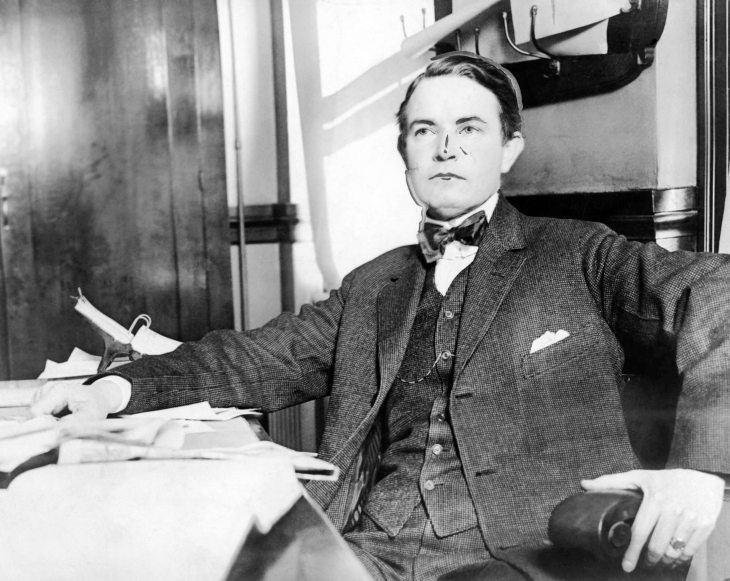

It was a remarkable career, filled with prominent cases and controversy, and, not long after ill health forced him to resign as Los Angeles County’s district attorney, Thomas Lee Woolwine died in June 1925 at just age 50. The featured artifact from the Museum’s collection for this post is a press photograph, date stamped 11 April 1919 for the reference department of the Newspaper Enterprise Association though the photo was taken for Central News Photo Service.

As the caption stated, the reason for the image was one of Woolwine’s crusades targeting civic leaders in Los Angeles, in this case, Mayor Frederick T. Woodman, who was accused by the DA of taking bribes. The wording here is, “THOMAS L. WOOLWINE, District Attorney of Los Angeles, Cal. who says that [a] plot to defeat justice is hatched by the officials and who is determined to prosecute Mayor Woodman on the famous bribe charge eminating [sic] out of the recent primary elections.”

Woolwine was a native of Nashville, Tennessee, the son of “Professor” Samuel Woolwine, an educator and college president. In spring 1896, he migrated to the Angel City to join his father’s brother, William, who moved from Nashville to San Diego in 1886 and then was a cashier at the Southern California Savings Bank before going on to work at the Los Angeles National Bank and the National Bank of California, where he became vice-president.

Woolwine became a clerk for District Attorney Frank P. Flint, serving in that role from 1897 to 1900. That latter year he married Alma Calvert Foy, daughter of the first saddler in Los Angeles, Samuel C. and sister of the first female librarian in the Angel City, Mary, who also became prominent in the city’s political circles. The couple were childless, but adopted the son of Woolwine’s brother, Samuel, Jr., after the baby lived and the mother died and the young man was raised as Thomas Lee, Jr.

In the early years of the 20th century, Woolwine went back to Tennessee and earned a law degree from Cumberland University, east of Nashville, and followed that with postgraduate work at Columbian University, renamed George Washington University in 1904, the year he completed his studies. He returned to Los Angeles with his wife and newly adopted son and took up a private law practice.

The ambitious young man, however, became deputy city attorney in 1907 and, the following year, became the Angel City’s prosecuting attorney while also taking on the duties of deputy district attorney for the county. He quickly made a name for himself as a crusader against vice, alcohol and public corruption and did not hesitate to take on powerful interests. His raid of the prestigious California Club, whose members constituted many of the elite of Los Angeles, because he alleged it illegally served alcoholic beverages caused a major controversy.

So, too, did his first run at elected office. A Democrat of the Southern school with influences from his home state, Woolwine was also an avid proponent of the Good Government movement. He was also a highly animated and passionate public speaker, with a penchant for the sensational. It was with no little amount of attention-grabbing that he announced he was challenging his boss, District Attorney John D. Fredericks, for that position in 1910, but he also charged that Fredericks failed to stop or covered up graft and the theft of taxpayer monies with the Los Angeles Aqueduct, roads projects, bond issues, and the machinations of recalled Mayor Arthur C. Harper.

Fredericks won the election and Woolwine returned to private practice, but he ran again for District Attorney in 1914 when Fredericks unsuccessfully challenged Hiram Johnson for the governor’s chair and emerged victorious. In eight years and winning two successive reelection campaigns in 1918 and 1922, Woolwine made headlines for his high-profile investigations and prosecutions, including of mayors Charles E. Sebastian and Woodman.

While the former was indicted by the district attorney’s office on charges of subverting the morals of a minor and was acquitted, he resigned after about fifteen months over an affair with a woman involved in the earlier legal issue. Remarkably, Sebastian, who was the chief of police before becoming mayor, was hired by Woolwine to work on the investigation of Woodman, accused in spring 1919 of accepting bribes. Woodman resigned and the rescinded his decision and faced a trial, with Woolwine making some crucial mistakes during the proceeding and the mayor was found not guilty.

Among his other high-profile cases were the convictions of deputy sheriffs Walter Lips and and Andrew Anderson for taking bribes; trials involving those who were part of the bombing of the Los Angeles Times Building; taking on the International Workers of the World, or I.W.W., a very left-leaning labor organization that incurred the wrath of the pro-business and anti-union Los Angeles Times and others, with some fifty prosecutions; and an aggressive move against the reconstituted Ku Klux Klan, which, with the rise of conservative Republican Party political dominance, briefly recruited a large number of members in greater Los Angeles. Even City Council President Ralph Criswell was said to have completed a questionnaire and membership application to join the KKK.

Woolwine, who evidently was hands-on with virtually any cases handled by his office, was also involved with some of the best-known and notorious criminal matters of the era, such as the unsolved murder of the prominent film director William Desmond Taylor, the prosecution of the infamous murderer, “Tiger Woman” Clara Phillips, and the trials of Madelynn Obenchain and Arthur Burch for the killing of her husband.

Referred to as a “stormy petrel” and the “Fighting District Attorney,” Woolwine was also threatened with grand jury investigations based on accusations made by enemies. He was also involved in fisticuffs with defense attorney in the courtroom on a couple of occasions and was found guilty of contempt by one judge for what was considered unseemly behavior in confronting opposing counsel. When his dog got into canine battles with a neighbor’s pooch, it was alleged that the District Attorney threatened his neighbor with a pistol, though the matter soon subsided.

His ambitions extended to seeking the chief executive’s office at Sacramento and he touted his bond fides as a fighter against vice and corruption in entering the Democratic Party field in the primary campaign in 1918, though he finished third. Four years later, he entered the ring again and, this time, secured the Democratic Party nomination. In the runoff, with a Socialist candidate garnering minimal support, Woolwine lost to Republican Friend W. Richardson by nearly 230,000 votes.

It was during this second run for governor that another controversy involving the DA erupted. In May 1922, he abruptly and without expressed reason fired Ida Wright Jones, who worked as an investigator for the district attorney’s office for some fifteen years. Woolwine then claimed that Jones sought to extort him for $10,000, while she charged that the two were lovers for several years.

He turned to the county’s Civil Service Commission with a formal complaint and the resulting investigation cleared him. Jones, however, responded with a lawsuit claiming that she’d been subject to libel by Woolwine and newspapers that reported details on his accusations against her. When the county Superior Court dismissed the case because of a lack of evidence as well as a ruling that there were privileged communications that could not be used as evidence, she appealed to the state Supreme Court, albeit without success.

Jones filed another suit against a Los Angeles newspaper and lost that at the local and appellate court levels and was also unable to secure back pay for the salary she said would have bene paid to her if she’d remained on the job. As with the Phillips and Obenchain cases, my colleague Gennie Truelock has, in the Homestead’s “Female Justice” series of presentations on women and the courts, given a talk on the Jones saga. It and the others are among the roster of recorded presentation available on the Museum’s YouTube channel.

As Los Angeles County grew enormously in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the job of district attorney grew correspondingly more complex, but also more politicized. Woolwine was the 27th person to serve in that office and his predecessor, Fredericks, held the job far longer, a dozen years, than anyone before him. Woolwine was in the role for eight years and almost certainly would have stayed longer—for one thing, his third term was slated to end in 1926, at which time he would have matched Fredericks.

In early 1923, press reports indicated that Woolwine was considering a well-paid job offer in Hollywood for a Independent Producing Manager’s Association on a five-year contract, though that did not pan out. He then requested and rescinded a request for an extended leave of absence, focusing mainly on the fact that he had not taken a vacation since he took the job eight years before while allowing that his health had been suffering in recent years, while the toll of the pressure on him was enormous.

While Woolwine finally did take a vacation, leaving his deputy, Asa Keyes, a twenty-year veteran of the department in charge, and then returned to work, he resigned on 6 June. His official statement was:

The people have, on three occasions, honored me with their suffrage by making me district attorney of Los Angeles county. For the vote of confidence I have always felt a most profound and sincere gratitude. In turn, it has been my constant endeavor to serve them faithfully and well.

In my great desire to carry out my oath of office, I have overworked and taxed my constitution to a point where I have become physically unable to give the affairs of the district attorney’s office that vigorous and conscientious treatment that I hope has characterized my official life.

I have not been a well man for some months and my physical condition has grown worse as the time passed . . .

A very serious condition has finally shown itself, resulting in a rather alarming stomach and digestive trouble, accompanied by severe hemorrhages of the stomach and intestines. I have been informed by several physicians that to remain in office under the strain necessarily incident to my official duty might result in my death and certainly would make it impossible for me ever to recover.

After adding that he was leaving the office to Keyes who had “signal ability and integrity,” though, in fact, his successor was later convicted of bribery in the notorious C.C. Julian oil stock scandal and served time at San Quentin, Woolwine stated that, after a period of quiet and rest, be intended to return to a private law practice.

After some five months of the peace and quiet at home, Woolwine, his wife and their son left for what was intended to be a four-month European tour, but the trip lasted nearly a year because his health became so precarious that the time had to be right for his return. When he finally arrived back in Los Angeles in August 1924, he was taken off a train on a stretcher, though his condition improved to the extent that he could take car rides and brief walks.

On 8 June 1925, several days after he took a serious turn for the worse, Woolwine died at his home. Keyes was quoted as saying, “during my years of association with him, I have come to love and respect Mr. Woolwine as did all who knew him. A splendid man he was—a lover of his country, a sincere, honest, conscientious public official who truly gave his life in its service. His death is a serious loss to the people of this county.”

Since Woolwine’s tenure, there have been four district attorneys who have served as long (that is, two terms or eight years) and only two that served longer (three terms and twelve years.) The current DA, George Gascón, has been criticized heavily for being too soft on prosecuting criminals, especially as violent and property crimes have skyrocketed recently, and a second recall effort has until 6 July to garner the required number of signatures for a recall to be put on the November ballot.

Woolwine was certainly one of the more notable of those to hold the office up to that time and his years in office were filled with frequent successes, press-worthy miscues and missteps, broad political ambition, pugnacious physical altercations and much more. He also published short stories and a 1909 novel, In the Valley of the Shadows about a love story amid a family feud in the mountains of his home state.

This photo shows him perhaps at his prime, pursuing another prosecution of a prominent political figure and not that far removed from winning his third term, the completion of which would have matched the longest period of service in the office by his nemesis, Fredericks. He may not be well-known today, nearly a century after his death, but he certainly was among the most prominent Angelenos of his day.

Paul, thank you for another excellent article. I’ve come across Thomas Woolwine’s name before, but I had no idea of the interesting role he played in LA history. Your article reminded me of one of my favorite LA attorneys, Earl Rogers, who was active in the 1910’s. And, of course, his journalist daughter, Adela Rogers St. Johns. Both lived pretty colorful lives! Best, Art Dominguez

Thanks, Art, for the comment and we’re glad you enjoyed the post. Woolwine certainly tussled with Rogers, who was a courtroom “performer” of the highest order. We have a court transcript from a very interesting 1903 murder case in which Rogers was a defense attorney, so we should definitely write about that in early July when that trial took place! We also have some Photoplay magazines with articles Adela wrote, as well as one of her books, so that’s another good future post.