by Paul R. Spitzzeri

Twenty years after the film industry arrived in Hollywood, its rapid growth and development was probably no better accentuated than through the fan magazine. The most popular of these in the late 1920s was Photoplay, which got its start in 1911 as one of the first of its kind.

In its early years, the magazine, however, exemplified what its title indicated: it focused on the plots and characters of films. By the end of the 1910s, however, it was reformatted into a publication that highlighted the private (or what was passed off as this) lives of the stars, as well as promoted films, studios and related aspects of the industry. The meal ticket for all film magazines, however, was the film star (or the many up and coming stars) and the gossip for which fans clamored.

This “That’s a Wrap” entry looks at a particularly interesting issue from the Homestead’s collection of Photoplay, because the December 1929 issue, among other elements, paid some attention to the question of what sound through the relatively new “talkies” meant to some of the industry’s biggest names, particularly women.

So, the very colorful and evocative cover image featured Norma Talmadge, of a famed film trio of sisters, speaking into a microphone and a title at the right reads “The Microphone—The Terror of the Studios.” The accompanying article by Harry Carr, using the highly (over)active, breezy, and slang-filled language favored in such publications, cited Clara Bow, one of the biggest actresses of the era, as an example of how “Mike” instilled fear in performers whose voices were not particularly well-suited to the use of sound.

In fact, the piece began with:

This is a story of Terrible Mike, the capricious genie of Hollywood, who is a Pain inthe Larynx to half of filmdom, and a Tin Santa Claus to the other half! — who gives a Yoo-Hoo There Leading Man a Voice like a Bull, and makes a Cauliflower-Eared Heavy talk like an Elfin Elbert, the Library Lizard! — and who has raised more hell in movieland than a clara bow in a theological seminary.

That snippet is an excellent example of the snappy prose found in many a film mag article and the reference to Bow and the seminary refers to her sex appeal in films like 1927’s It, which stirred no little controversy in a decade that juxtaposed a strong current of conservatism with a rising tide of the flouting of social tradition.

Bow’s problem, though, was that, according to many accounts, she detested sound and, while filming her first talking picture, The Wild Party, released in April 1929, it was stated that she nervously looked at “Terrible Mike” during shooting. Reviews of her performance in a talkie were decidedly mixed, with some commentators highlighting her Brooklyn accent and a harshness of tone. It didn’t help that production of the movie was rushed and Bow, it was reported, was given only a couple of weeks to prepare for the new technology of sound.

In talking about Bow, Carr wrote, “And so Clara Bow says she’s planning to take a year’s trip abroad when her present contract with Paramount ends,” and then puts her on a “see-saw” with another screen siren, Bebe Daniels. Carr continued, “Bebe is on the end that’s going up, and Clara is — well, er, let’s confine ourselves to her own admission that she’s going to take a European trip by and by because she’s tired.

In discussing her performance in The Wild Party, Carr focused on her first scene, in which she rushed into a college dormitory full of women and cried out “Hello, everybody!” In Carr’s telling,

the sound-mixing gentleman in the monitor-room above the stage, not being familiar with the — ah — er — vibrations of Clara’s voice, didn’t properly tune down his dials for Clara’s words . . . and every light valve in the recording room was broken.

Bow didn’t continue making talking films for a couple more years and retained much of her following, but, in 1931, with her Paramount contract concluded, she entered a sanitarium. A short-lived return ensued, but, by 1933, still in her twenties, her career was over. Married to cowboy actor Rex Bell and the mother of two children, Bow tried to commit suicide in 1944 and spent more time in sanitaria. She died at age 60 in 1965.

As for the actress featured in the cover, Norma Talmadge also struggled with the move from silents, where she was a majot star, to sound productions. Within a year of the appearance of the beautiful cover by Earl Christy, whose work adorned many Photoplay covers, her career was over.

The other cover article was “You Can’t Get Away With It in Hollywood,” another breezily penned confection by Basil Woon that lampooned the ubiquitous gossip that permeated Hollywood then, as now (though now much of that is handled in social and digital media). Woon wrote of rumors in the film community of his imminent divorce and introduced characters like “Hector Snooparound,” “Patricia Peekaboo,” and “Susie Snoop” as part of his yarn. In penning a conversation with his wife about a meeting Woon was to have with studio chief Irving Thalberg of MGM, Woon wrote that his wife, shutting down his explanation of the meeting, exclaimed:

What you did . . . was to leave the Roosevelt [Hotel] with that terrible Bugs Baer. You got in a Cadillac with two girls in it. One of them was Lucille Lush and the other was Bridget Brilliantine. You were with Bridget. After that you went over to Bert Wheeler’s with Tom McNamara, and you had a lot of drinks. Then you and Tom and another girl named Helen Hugg went to Billy Hayne’s place at the beach . . .

Of course, Mrs. Woon got all of her information on her husband’s shenanigans from rumor, innuendo, and gossip.

Other interesting material in the magazine included reviews of new films, including Janet Gaynor’s Sunny Side Up; featured songs from new movies; a feature about the problems encountered by actors who were made famous in films directed by the legendary D.W. Griffith (whose career was on the downslope by 1929); the pluckiness of actress Alice White, whose career ended within a few years, as well; and one about four rising stars in the business, the only of which who became well-known being Robert Armstrong, the male lead in 1933’s King Kong, and who had a long career in film and television.

One stand-out, given the debate today about the lack of opportunities for women in film and, perhaps, a subtext in the sex harrassment scandals now rocking the industry, is a piece by Charleson Gray that was a rebuttal to a September Photoplay article that claimed Hollywood was “a manless town.” Gray’s answer was as rapid-fire and slang-filled as the others cited. Here’s his opening salvo:

So Hollwood is a manless town, is it? And the picture girls lean on their chins and sigh wanly for a romance unsupplied by local lads, do they? Whilst their bright and langorous eyes inspect incoming trains for boy-friends not connected with the film racket, is that it? Boy, my Howitzer! My black-jack, machine gun, and kris! My Big Bertha and bullet-proof vest! We sally forth to talk back. The starlets have bitten the hands that feed them. And they must be shown that the hand which feeds may also spank.

Gray speaks of “the film cutie” as a “shameless hussy” and “beautiful with the beauty of the last illusion” and castigates female actresses for not treating their male colleagues with the respect they deserved. This is all done, though, with the guise of humor, so the reader had to determine how much of this to take seriously.

Amidst the gossip, the fixation on the stars and their private lives and transitions to sound, and the serio-comic debate about gender, there was one brief piece of technical note. This had to do with the recent development of a new type of film that doubled the width, and, therefore, dramatically improved the resolution of the visual and audio impact of the recorded images.

Developed over three years by William Fox, of Twentieth-Century Fox, and partner Theodore Case, as the Fox-Case Corporation along with General Theatres Equipment, Inc., the film, dramatically titled “Grandeur,” was touted as a product that “is going to revolutionize the making and showing of motion pictures.”

Used for a Movietone News newsreel and Movietone Follies, both shown before main features, the film was said to employ “astounding effects” that “thrilled a hardboiled audience.” Unfortunately, with the article appearing just after the crash of the stock market that ushered in the Great Depression, Grandeur’s future was not as “limitless” as advertised and the product fell victim to the worsening economy within a few years. There was a comback of the wider film type in the 1950s by Mike Todd and his “Todd-AO” system and one by Panavision, but its use has been sporadic due to costs for the film, the projectors and the screens.

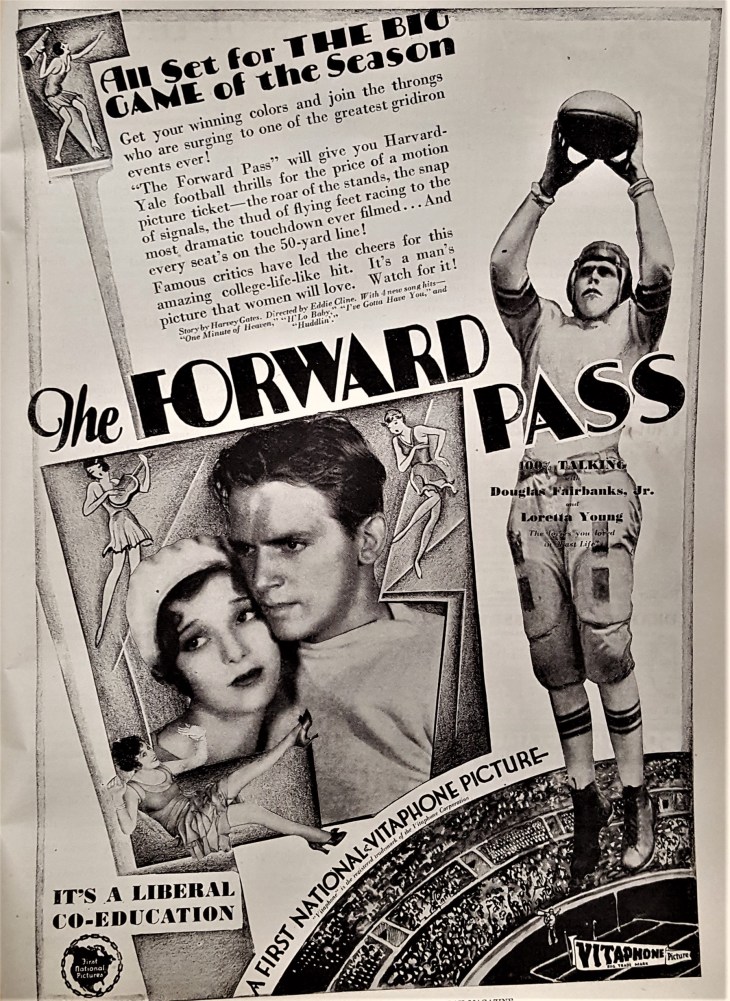

Finally, because advertisements pay principally for the costs of publications, there are a wealth of interesting advertisements, including ones that highlight star endorsements, promotions of new films, and those that advertise for the Christmas season. Especially with these ads, it is notable to see the change in design, including the use of different type fonts and the rise of Art Deco elements. Perusing the ads in the publication, as well as the content of many of its features, it is also very clear that a majority of the readers were women.

As noted above, film magazines like Photoplay and its many competitors are excellent sources for information (and mythology and legends) about Hollywood and the film industry, but also the era. Gender roles, societal norms and mores, marketing and public relations, consumerism, and economics are just some of the many areas of American life that are highlighted in the publications.