by Paul R. Spitzzeri

Today is the 178th anniversary of the Rowland and Workman Expedition’s arrival into greater Los Angeles. The party was composed of a remarkably diverse group of people, including emigrants from New Mexico to Mexican Alta California, travelers who went along on their way to somewhere else, and, in one markedly different case, an 18-year old ornithologist (a scientific student of birds) named William Gambel.

Twenty-five years ago this month, I had the pleasure of making a return visit to the Bancroft Library, one of the great archives in our state, at the University of California, Berkeley, and spending a day pawing through old records pertaining to the Workman and Temple families.

Easily one of the most intriguing and compelling finds were two letters and a short biography of Gambel, the originals of which are in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and copies of which the Bancroft kept in its holdings. The letters are particularly interesting as they are rare contemporary artifacts relating to the expedition and provide some great content about the trip and the young man who traveled alone while still in his teens and joined the group.

Gambel was a native of Philadelphia, born there in June 1823. His parents, William, Sr. and Elizabeth Richardson were both Irish immigrants and the couple had two daughters in addition to their son. Gambel, Sr. died of pneumonia when William, Jr. was eight years old and Elizabeth supported her family by teaching. The young man “early manifested an aptitude for learning, acquiring a good knowledge of Latin and Greek,” according to William Middleton, a nephew who composed the four-page biographical sketch of Gambel.

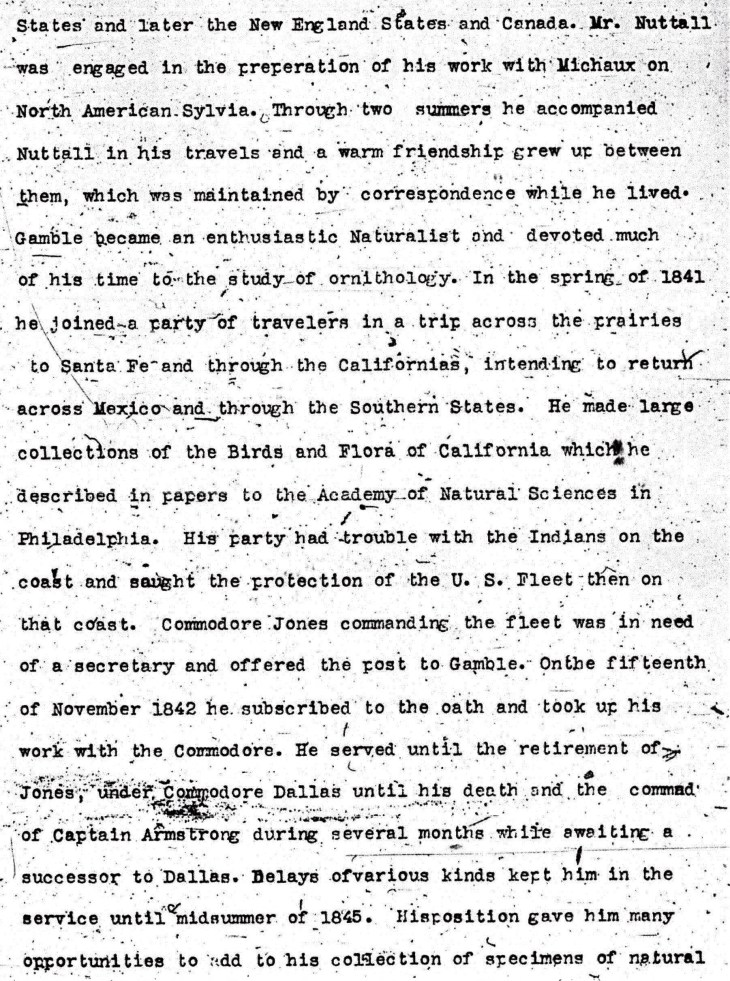

His interests in zoology “attracted the attention of Thomas Nuttall,” who was a well-known name in the field and, before he turned sixteen, Gambel joined the famed naturalist on his field work, including in New England, Canada, and the South Atlantic states, during the summers of 1839 and 1840. As a result, Gambel “became an enthusiastic Naturalist and devoted much of his time to the study of ornithology.”

Middleton added, “in the spring of 1841 he joined a party of travelers in a trip across the prairies to Santa Fe and through the Californias, intending to return across Mexico and through the Southern States.” After arriving in California, Gambel “made large collections of the Birds and Flora of California which he described in papers to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.”

First, however, there is a letter he wrote to his mother from Santa Fe and dated 25 July 1841. Because he’d been on the trail, likely from the start of the Santa Fe Trail from near modern Independence, Missouri, for some time, he began by observing “it has been so long since you have heard from me that you must nearly have forgotten me, but ’tis different with me when standing Guard in among Indians.”

The teenager added, “I woud often think of home—the dangers I was in. I sometimes feel sorry that I left it.” He talked about his caravan meeting some 500 Arapaho warriors on the trail and that the travelers got through “by giving them a great many presents.” Then, as they neared the Rocky Mountains, some 400 Paiutes attacked the train “and as being only 90 men in all [we] had a great deal of trouble to get clear of them” with the young man recording that gunshots fell near, but did not hit, the caravan.

There was privation, as “we also suffered much from want of water sometimes having to do without it for two days.” Still, he noted, “I have got through with safety . . . but now I am only half way to where I am going.” Adding that this mother need “not mind it, I shall get some safe in due time if God is willing,” he wrote:

It is to California, I am going straight across the country to there and from there to Sandwich Islands [Hawaii] and from there a five months voyage round Cape Horn to the no[rthern] states. When I get to California I will write to you but will take the letter 5 or six months to go to you, besides the time I am going from her to there which will be 3 perhaps, so you will heare [sic] from me again in about 8 or 9 months and see me back in perhaps 10 months. It is a very long while but I cannot help it as I cannot go in railroads but dog led on a mule from morning to night.

He noted that he wouldn’t be leaving Santa Fe for another month “since if another company foes in this fall I will write to you again from here.” That month would be an interesting one because “I am now in a different county now having to speak the Spanish language altogether. I have studied it a great deal and now can speak pretty well.” He added that “the manners and customs are also very different but any thing suits me.” Remarkably, he told his mother “I would as soon live here nearly as in Philadelphia.”

Added to the letter was a receipt from 15 April 1841 documenting that Gambel bought a mule for sixty dollars, a large sum, and then the young man added a note that “she proved a very faithful and excellent old animal though he ears were very long.” He sold the animal for $25 in Santa Fe and added that “she went back home again over the same weary road.”

Gambel’s estimate of remaining in Santa Fe a month was about right and the fall company he joined was the Rowland and Workman party, which left the 1st of September and took the Old Spanish Trail for its journey of more than two months. He did not write his mother right away, but did pen a missive from “Pueblo de los Angeles, Upper California” on 14 January 1842, a little over two months after arrival in the pueblo.

His letter began much as his previous one did: “It has been so long since you heard from me you have perhaps given me up for lost, but thank God I am yet safe, though so far from home.” He noted that the trip out to the coast “was a long and dangerous journey” but “I have got through without sickness or accident.”

Gambel added

we left Santa Fe the 1st of September and arrived here the last of November going three months travelling over rocky mountains, barren deserts, worse than those of Arabia, sometimes having to do without water 2 & 3 days at a time, and towards the last almost starving in want of provisions, suffering also innumerable other difficulties, which I have not time to mention, but am glad I have got through them safe and am in California on the banks of the broad Pacific basin from where I shall go home in a vessel perhaps round Cape Horn. If not I will go to Panama and from there across to the west Indian Islands [Caribbean] and from there home.

The reference to an arrival in late November may mean that the expedition reached the fertile plains of the Inland Empire and San Gabriel Valley and then stayed in these outskirts of Los Angeles for a period before making the final leg to Los Angeles. It is also interesting that the youngster stated the deserts, such as the Mojave, were worse than those of Saudi Arabia, which, of course, Gambel had not seen!

Meantime, he planned to stay until the late summer and not depart from California until August or September. Because a ship landed “in the port of St. Pedro about 30 miles from here and sails in the morning” he had to make his missive short. He also planned to write Nuttall and another friend and then asked about his sisters and mother. He was pleased to say that he was in a fine state of health “not having been a sick a day since I left, though I have been knocked about in all kinds of weather, and have lived almost as rough as an Indian.”

Gambel then had interesting information to convey about the land in which he found himself:

California is a fine rich country and to which many western people is [sic] now commencing to emigrate, and in a few years I expect it will be under the Government of either the British or Americans. They raise an immense number of Cattle and horses here which you can buy for almost nothing, a good fat ox only costing 3 dollars and you can take the hide to a store and sell it for 2 dollars so that the meat only costs a dollar. The best horse can also be bought for from 5-10 dollars and mares from 1 dollar to 2 dollars. If our Yankee farmers were here they could soon make their fortune instead of cultivating the poor rocky soils of Conneticut [sic] and Vermont.

Because of the rush to get his correspondence down to San Pedro, he apologized for having to close “although I could fill 20 letters” and he hoped to write longer missives when the next vessel arrived. After signing his name, he added a postscript that should not be a surprise from a son with two younger sisters: “Give my love to my Sisters and tell them not to give them too quick to any young fellows they may come across.”

Gambel did not return by a late summer sea voyage as planned. Instead, while making trips to study the flora and fauna of California, Middleton wrote, the young naturalist “had trouble with the Indians on the coast and sought the protection of the U.S. [Navy] fleet then on that coast.

Commodore Thomas Ap Catesby Jones was in command and “was in need of a secretary and offered the post” to the young man, who began his duties just a month after Jones mistaken seized Monterey in October 1842 on the mistaken assumption that war had broken out between the U.S. and Mexico. Jones quickly apologized for the error and sailed away and Gambel remained with him until the commodore retired.

Gambel then served under Commodore Alexander J. Dallas until the latter’s death at Peru in June 1844 and for several months for a temporary successor. It was not until mid-1845 that the naturalist left his post, which took him up and down the coast and to Hawaii and during which trips he continued to gather specimens for his growing collection. These included native Peruvian skulls, as well as plant materials and bird specimens.

While still in the service of the Navy, Gambel was elected, in late August 1843 to membership with the Academy of Natural Sciences in his native city. Having studied medicine with the ship surgeon while on the Pacific coast, Gambel returned home and, after preparing his specimens for exhibition at the Academy, studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned his doctorate in 1848.

Shortly afterward, he married Catherine Towson of Philadelphia and was recording secretary for the Academy. Though he tried to open a medical practice, he encountered some financial challenges and “with the gold fever of ’49, the Wanderlust again attacked him.” After just six months of marriage, Gambel was “again in the saddle on his way to locate in the new city of San Francisco, California.”

He brought his books and other materials for his profession as a doctor and sent them by ship around the Horn, while he took the northern land route known generally as the California Trail. He got to what Middleton called the “Rio de las Plumas”, or the Feather River, in the gold fields, but “fell in with a party which was suffering with Typhoid Fever.”

Gambel ministered to his fellow travelers but “after rendering them what service he could he himself went down with the disease and died” on 13 December 1849. He was buried under a pine tree but the grave site was later erased by hydraulic mining. Still, he is remembered for his pioneering work as a naturalist in what became the American Southwest, while his letters before and after the Rowland and Workman Expedition are less-known, but very interesting and informative.