by Paul R. Spitzzeri

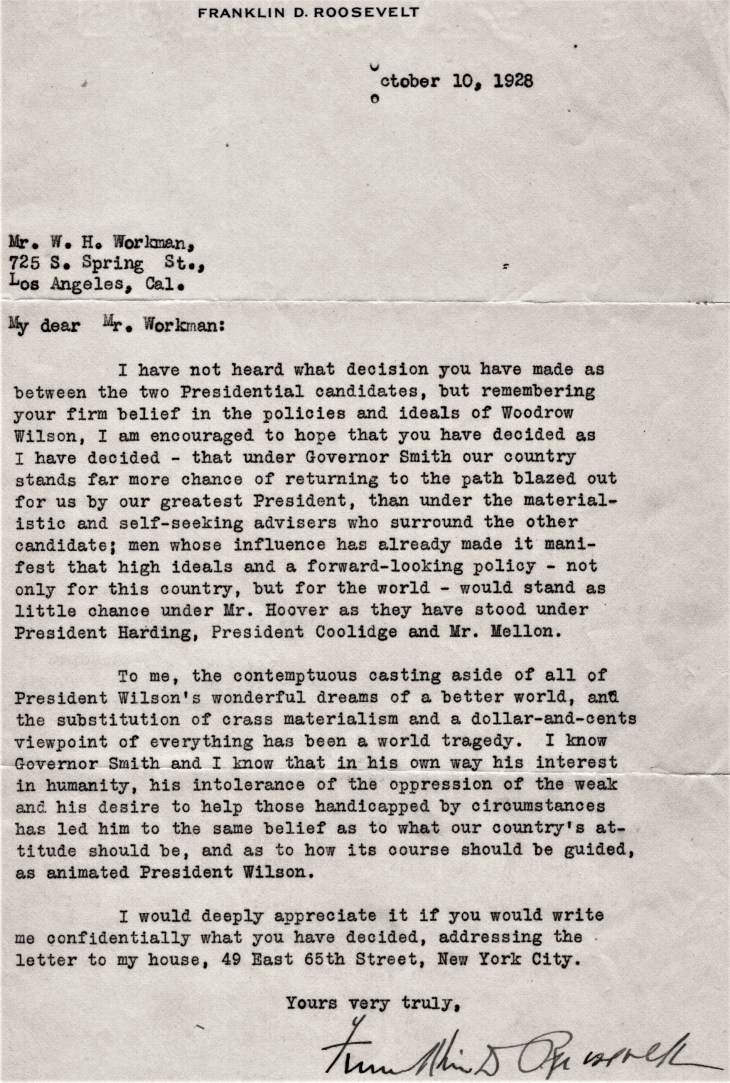

During this most remarkable of presidential election seasons, we continue to highlight artifacts from the Homestead’s collection that concern previous campaigns, most notably that of 1928. One remarkable object is a letter to William H. Workman, Jr. from Franklin Delano Roosevelt and dated 10 October 1928.

Workman, born in Los Angeles in 1874, was the fourth of seven children of Maria E. Boyle and William H. Workman, who resided on the estate left to Maria by her father, Andrew Boyle, and known as Paredon Blanco, for the white bluff on the east side of the Los Angeles River across from downtown. The year after young William, Jr. was born, his father and partners John Lazzarovich and Isaias W. Hellman established Boyle Heights.

William, Jr. was raised on the family estate, which had vineyards and other crops while his father continued his activity in Los Angeles politics, serving as a member of the school board and city council before winning election in late 1886 as the city’s mayor. This occurred as the famed Boom of the Eighties took place with a large influx of new settlers and the attending building of houses, businesses, and other elements.

Meanwhile, William Jr. began high school just as his father’s two-year mayoral administration ended and, after graduating from Los Angeles High, he went to St. Vincent’s College, a Catholic institution that later became Loyola Marymount University and from where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. He then studied engineering at Stanford University, which was opened in 1891, and completed a four-year course in just half that time. He was hired by the Southern California Power Company, which became part of Southern California Edison after a short while, and he rose to be assistant to the firm’s president.

Just after the turn of the 20th century, however, William, Jr. decided to quit his job and traveled around the world. In 1903, he stopped at Peking (now Beijing), China to visit a friend, Thomas Haskins, who worked for the American consulate. While there, he saw a photo of Haskins’ beau, Elizabeth Gowan, a San Francisco resident, and remarked that it was a good thing he wasn’t meeting her in person other “I’d take her away from you.” Haskins replied “the devil you would—try and do it.” Haskins and Gowan married and lived in China until his early demise there after several years.

Workman, who worked for Union Oil Company in San Francsco, then courted Elizabeth for quite some time and, while she resisted for some time, the couple married in 1909. They were married for over forty years and had four children, while Workman ran a real estate firm and then, after his father’s death in 1918, managed the estate. In 1919, he helped organize, as secretary and general manager, a Morris Plan Bank, an institution which specialized in loaning to people who could not obtain funds from traditional banks.

He was president of the enterprise when he received this letter and while Workman did not hold political office, his sister, Mary Julia, was active in Democratic Party circles in the Angel City, while his brother, Boyle, was president of the Los Angeles City Council for most of the Twenties. It wasn’t as if, however, Workman was politically inactive. Like his siblings and father, he was a moderate Democrat and was a supporter of Republican Hiram Johnson, a California governor and U.S. senator. He also served on the Los Angeles Planning Commission and the Municipal League.

In 1919, however, as Johnson looked to secure his party’s nomination for president, Workman publicly published a letter to him, saying that he’d told others he was considering voting for the senator if he became the nominee, but criticizing Johnson’s opposition to the League of Nations and blasting him for having “lost your vision” and having become “simply an obstructionist.” So, it wasn’t particularly surprising that he was contacted by Roosevelt, the rising star of the Democratic Party during the era.

Roosevelt was born in 1882 to a wealthy family dating back to the Dutch colonization of New York and lived in life of privilege that included home schooling and attendance at a prestigious private academy. He entered Harvard as the 19th century came to a close, but was an average student. His fifth cousin, Theodore, was president for most of that first decade of the new century and Roosevelt married the president’s niece, Eleanor, who did charity work with New York City’s poor, in 1905.

After an undistinguished period at Columbia Law School, Roosevelt worked for a New York City law firm as a clerk, but was not enthused by his work. Inspired by his distant cousin, however, he entered politics and ran for the state senate in 1910, though he was a Democrat and Theodore’s branch of the Roosevelt clan were Republicans. Roosevelt won election at 28 and found his calling and his footing, as he moved away from his privileged background and, with encouragement from Eleanor, became a Progressive.

In 1912, when he won reelection, Roosevelt was a supporter of New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson in his bid for the presidency and, when Wilson won, with a three-way race involving Theodore as a third-party candidate (not unlike, say, the 1992 campaign), he appointed Roosevelt Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He took to his position with great enthusiasm and was a strong advocate for building up the Navy. When America entered the First World War, Roosevelt earned a reputation as a highly able administrator during the war effort.

With these burnished credentials, Roosevelt, who was only 38 and just a decade into his political career, became the Democratic Party candidate for vice-president alongside James M. Cox in the 1920 campaign, though the Republicans, headed by Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, won easily. Roosevelt returned to New York City and entered the business world. Just a year later, however, he was stricken with polio and underwent an intensive recovery to regain physical activity, though he was never able to use his legs to walk unaided.

With his political career sidelined as he dealt with his health, Roosevelt kept his irons in the Democratic Party fire, with much assistance from his wife despite the change in their relationship as became unfaithful. In 1924, he spoke at the party’s national convention to nominate New York Governor Al Smith for president and, though this was unsuccessful, Roosevelt did so again four years later when Smith secured the nomination. The governor, in turn, encouraged Roosevelt to run to replace him as the Empire State’s chief executive.

It is not known how well Roosevelt and Workman knew each other or how they became acquainted and the letter’s address to “My dear Mr. Workman” suggests that their relationship was not personal, but strictly political, given Workman’s prominence in local Democratic Party politics. Moreover, as was the case throughout the Roaring Twenties, the Democrats were in a very poor position in challenging the near-total supremacy of the G.O.P. in local politics, even more so than in much of the rest of the United States (excepting the South, where conservative Democrats were dominant.)

In any case, Roosevelt began his missive by stating that he had not been apprised of Workman’s decision on who to support for president in 1928, but “remembering your firm belief in the policies and ideals of Woodrow Wilson, I am encouraged to hope that you have decided as I have decided—that under Governor Smith our country stands far more chance of returning to the path blazed out for us by our greatest President, than under the materialistic and self-seeking advisers who surround the other candidate.”

Moreover, Roosevelt continued “high ideals and a forward-looking policy” for the United States and the world “would stand as little chance under Mr. Hoover as they have stood under President Harding, President Coolidge and Mr. Mellon.” The last was Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, the powerful Pittsburgh banker and steel and aluminum industrialist whose tax cuts and pro-business policies were credited with spurring much of the economic boom of the Twenties.

Roosevelt continued that “the contemptuous casting aside of all of President Wilson’s wonderful dreams of a better world” in favor of the Republican Party’s platforms engendering “crass materialism and a dollar-and-cents viewpoint of everything” was nothing less than “a world tragedy.” Counter to this was the “interest in humanity,” “intolerance of the oppression of the weak,” and “desire to help those handicapped by circumstances” exemplified by Smith, who would, it was averred, follow the same principles “as animated President Wilson.”

The letter ended with Roosevelt asking Workman “if you would write me confidentially what you have decided,” noting that if he would direct his reply to Roosevelt’s home address just east of Central Park (the townhome, built by Roosevelt’s mother as two identical units in one building, is now a public policy institute for Hunter College of the City University of New York,) “I would deeply appreciate it.”

We don’t know whether Workman replied and, if so, if his answer survives in the papers of Roosevelt. The 1928 campaign was another decisive Republican victory, with Hoover winning nationally by 17.5% and winning 40 of the 48 states with 444 electoral votes to just 87 for Smith. Hoover’s margin in California was 30 points and, in Los Angeles County, the margin was even bigger at over 40., with the Republican garnering over a half-million votes and Smith taking just 209,000.

Roosevelt, however, despite the red tide of Republican dominance, eked out a narrow victory in the race for New York governor, winning by just 25,000 votes. His emphasis on such policies as lower utility prices and assistance to farmers in lowering taxes broadened his appeal outside New York City and led to a landslide reelection in 1930 (governors served two-year terms in the state at the time).

The worsening of the Great Depression and the perceived anemic response of the Hoover administration and the work of Mellon and his department led to a Roosevelt campaign in 1932 that resulted in swamping of the incumbent and the onset of Roosevelt’s New Deal and an unprecedented four victorious campaigns for president while dealing with the Great Depression and World War II.

While Roosevelt wrote of Wilson as “our greatest President,” a verdict almost no one subscribes to now, there are many who place FDR in the pantheon with such figures as Lincoln and Washington, though there remains vigorous debate about his legacy. Included in the Homestead’s collection is an invitation to Workman and his wife to attend the fourth inauguration in January 1945, just a few months before the 32nd chief executive died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 63.