by Paul R. Spitzzeri

The amazing ascent into wealth in the late 1910s and the resulting dramatic decline a decade or so later of the financial fortunes of Walter P. Temple are remarkable on their own, but they take on an additional striking resonance in recalling the similarities of his situation with that of his father, F.P.F. Temple, a half century before.

In the late 1860s and first half of the following decade, F.P.F. Temple, a highly successful rancher and farmer, turned his considerable energies to business as Los Angeles underwent its first boom, small in comparison to later ones, but highly significant for the time. Endeavors in oil, mining, railroads, real estate and many others were undertaken as Temple, by some accounts the wealthiest denizen of the Angel City, pursued projects in profusion during the period.

Much of this was financed through his banks, including Hellman, Temple and Company, the second institution to open in Los Angeles when it was formed in 1868. The “company” was silent partner, William Workman (accounted by some as the second richest resident in the region), Temple’s father-in-law, whose attention was mostly directed to his princely domain on over 24,000 acres of the Rancho La Puente. The managing cashier was the young, brilliant merchant, Isaias W. Hellman, among the early Jewish reidents of Los Angeles and who rose to great heights in California business and finance. It would have been best if Temple left the running of the bank to Hellman and enjoyed the proceeds of the younger man’s considerable acumen and skill.

Temple, though, wanted an active involvement and a divergence in loaning policy (Hellman subsequently reflected that remaining in the partnership would have left him poor) led to a sundering of the partnership. Hellman went on to form the highly successful Farmers and Merchants Bank, while Temple and Workman forged ahead with their own bank and the result, when an economic panic hit in 1875-76, was the institution’s collapse and city’s first large-scale business failure, being an unmitigated disaster of the two men and their families.

Walter was just six years old when the Temple and Workman bank folded and, while he grew up in straitened financial circumstances on a remnant of the family’s half of Rancho La Merced, he and his younger brother Charles inherited the fifty-acre Temple Homestead, just north of today’s Whittier Narrrows Dam, when their mother, Antonia Margarita Workman de Temple died in early 1892. A little more than a decade later, Charles sold his half of this brother and, Walter, newly married and soon to have four surviving children with wife Laura Gonzalez, often struggled to make a living as a farmer, teamster, and insurance agent.

His fall 1912 acquisition of sixty acres in the Montebello Hills, land owned by his father before the bank debacle and lost by foreclosure on a loan to the institution to Elias J. “Lucky” Baldwin, from Baldwin’s executor, Hiram A. Unruh, meant the sale of the family homestead. Temple, who couldn’t buy the new property outright and so made an arrangement to pay in installments, moved his family into an adobe home built in 1869 by Rafael Basye and which was once a saloon and billard parlor ran by his sister, Lucinda, and her husband, Manuel Zuñiga.

It was presumed that there was something of an “oil belt” running through the area with fields in Los Angeles (brought in by Charles Canfield and Edward L. Doheny in the early Nineties), nearby Whittier and the Puente Oil Company’s tract on William R. Rowland’s portion of Rancho La Puente, and down to Olinda in modern Brea all part of it. Apparently, El Monte merchant and real estate developer Milton Kauffman, an old friend of Temple, encouraged him to buy the Montebello Hills parcel and in less than two years, a staggering stroke of good fortune struck.

Thomas W. Temple II, Walter and Laura’s eldest child and a lad of just nine years of age, stumbled upon oil indication on the hillside the family called Temple Heights. Standard Oil Company of California, also leasing and drilling on the Baldwin daughters’ portion of the hills, brought in the first well on the Temple lease in June 1917. About two dozen more wells followed, including quite a few producers and a few bonafide gushers. The one-eighth royalty provided the Temples substantial wealth in short order and Walter soon invested in his own oil projects as well as real estate.

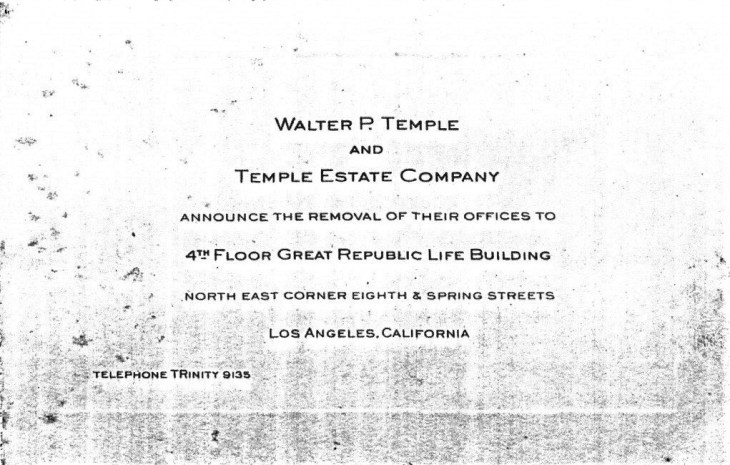

An outgrowth of the latter was the Temple Estate Company, organized at the end of May 1923, to manage all of Walter’s holdings outside of the newly established Town of Temple, formed that spring and renamed Temple City five years later, and which was governed by the Temple Townsite Company. For about three years, the Temple Estate Company was headquartered in the Great Republic Life Building at Main, Spring and Eighth streets, several blocks south of the Temple Block, built by Walter’s uncle, Jonathan, and father between about 1848 and 1871 and which was soon to be leveled for the construction of Los Angeles City Hall.

The Great Republic, which was named for the insurance company that was the anchor tenant, was built by a syndicate that included A. Otis Birch, an oil operator and furniture store owner; architects Albert Walker and Percy Eisen (who designed the eleven-story structure and many of Temple’s other building projects); Kauffman; Temple; and Temple’s lawyer, George H. Woodruff. The three, along with Alhambra rancher Sylvester Dupuy (whose “Pyrenees Castle” was once owned by the recently deceased music producer and convicted murderer Phil Spector), were the developers of Temple City, as well.

For several years, until the completion, in spring 1927, of the four-story Edison Building in Alhambra, the Temple Estate Company built a number of structures in that city, El Monte and San Gabriel and its offices moved to the Edison when it was finished. By then, however, the active accumulation of building projects, not to mention the separate oil projects, Temple City project, and extensive work at the Workman Homestead, bought by Walter in 1917, and including the five-year construction, at great expense, of the family’s Spanish Colonial Revival mansion, La Casa Nueva, caused mounting concerns about his financial health—especially as oil production at Montebello dropped as the decade entered its second half.

The solution in spring 1926 was to issue bonds for the townsite and estate companies and, while this raised the necessary capital to continue with in-process developments, there was the matter of meeting obligations on regular interest payments. If income from oil wells and rented and leased office and store spaces did not improve, the matter would, naturally, worsen. Within a couple of years, this is what happened and, despite earnest efforts to improve the situation at Temple City by hiring new sales agents and to bring in oil at such sites as the Ventura Avenue field between that city and Ojai, prospects darkened considerably.

The storm clouds got far more menacing as the decade came to a close. In late spring 1929, the company decided to issue another $200,000 in bonds after expanded its directorate to include Walter’s daughter, Agnes, who’d just graduated from Dominican College and married in the fall. About a month later, properties in Alhambra were sold for $450,000 to raise more capital, but it was evident that the downward spiral was quickening, especially after the crash of the stock market in New York that October that ushered in the Great Depression. The following spring, Temple decided to lease the Homestead to the Golden State Military Academy, which moved from Redondo Beach, and he packed up and moved to Ensenada in Baja California, México, where he could live more cheaply and hope his money matters would rebound. He, Kauffman and Woodruff were also stockholders of the Playa Ensenada hotel and casino project, which included Jack Dempsey as a prominent investor. The lavish facility opened on Halloween 1930, but after the abolishment of Prohibition three years later and declining visitation from Americans, it foundered and is now the Riviera de Ensenada cultural center and museum.

Kauffman and Woodruff, meanwhile, remained in Los Angeles and kept the Temple Estate Company in operation, while Temple was on his self-imposed exile and was president in absentia. Today’s featured artifact from the museum’s collection is a letter from Woodruff to Temple, dated 6 February 1931, less than a year after Temple decamped to Ensenada, and it shows just how dire the situation was.

The missive was simply addressed to “Mr. Walter P. Temple / Ensenada, Mexico” and on the letterhead of the law firm of Woodruff, Musick and Hartke, with offices in Los Angeles in the Security Title Insurance Building at 6th Street and Grand Avenue near Pershing Square. Woodruff (1873-1944) hailed from Connecticut but came west to attend college in Tacoma, Washington and then Stanford University. After a brief tenure running the state boys’ school at Whittier, Woodruff was admitted to the bar in 1902 and was briefly Whittier’s city attorney followed by stints as counsel for title insurance and trust companies in Los Angeles before he went into private practice in 1907. How he became Temple’s attorney is not known, but they were business partners and friends, along with Kauffman, for the entirety of the Twenties and into the Thirties.

Yet, Woodruff’s letter is blunt as he informed Temple that, after speaking with Maud Romero Bassity, Temple’s companion and who was in Los Angeles to see him personally, “I am awfully sorry that I am unable to give her any assistance from the funds of the Temple Estate Company.” This was simply because the firm “is fortunate to exist al atll, or at least to be able to retain and carry its assets,” which then included the Workman Homestead as one of the last holdouts. The lawyer went on that

we have been struggling along under the same adverse conditions that have prevailed ever since you have been away and we have about reached the point where there are no chips and whetstones left from which to get even money enough for your weekly allowance, so it is utterly out of the question to try to do anything more for Mrs. Bassity.

Woodruff then implored Temple to return to Los Angeles “and bring yourself up to date concerning the affairs to the Estate.” He added that “I do not feel like assuming the responsibility of making all necessary decisions . . . without your keeping pretty closely in touch with what we are doing.” He added that “everything is being done that is possible to do to conserve the interests of yourself and the estate,” but Temple’s involvement was need to approve or refect decisions.

The attorney then noted that meetings of the company’s directors and stockholders were urgently required and Temple had to be there to deal with issues from the previous year and those that would arise in the next one. He told Bassity that she should return to Ensenada “and bring you up here right away, because there are some matters that require immediate attention.

Woodruff expressed his regrets that “ntohing can be done to relieve the present situation, but I know of no remedy.” He added that he was doubtful “if any can be found until there is a change in the real estate market of such nature as will enable us to dispose of the real estate that the company now owns.” The problem, as noted above, was that all of that property “is subject to indebtedness which has to be met out of the proceeds of sales of the property efore anything will be available for you or anyone else.”

For this reason, nothing could be disposed of “at sacrifice prices to meet the emergency needs because all money that we would receive from sales,” no matter the price, “would apply in payment of the indebtedness and not be available for your use.” With this dour pronouncement, Woodruff closed with saying that he was glad to hear that Temple was doing well and that he would be happy to see him soon.

It is not known if Temple heeded Woodruff’s urgent request and traveled up to Los Angeles for the meeting, but what we do know is that the Depression worsened considerably into the next year, when massive waves of bank failures, skyrocketing unemployment, and other desperate conditions took place. In 1930, the Temple Estate Company mortgaged the crop of walnuts raised at the Homestead, a sign of how desperate conditions were. The 92-acre ranch was subject to a loan from the Bank of California and that institution filed for foreclosure. In July 1932, the bank took possession and, for the third time, following the Baldwin foreclosure of 1879 and one involving Walter’s brother John two decades later, the Homestead was lost by the family.

The military school, renamed Raenford, continued to lease the ranch for a couple more years but financial problems (many private schools, of course, suffered declining enrollments) led it to move to Encino. For the rest of the thirties, the Homestead was unoccupied, except for caretakers and it was not until fall 1940 that Harry and Lois Brown of Monrovia bought the ranch for their newly established El Encanto Sanitarium.

Temple meanwhile moved briefly to Tijuana and then to San Diego, but as he developed cancer, he and Bassity returned to Los Angeles and lived in a small residence behind her parents’ home in Lincoln Heights, where Temple died in November 1938 at age 69. The Bank of California refused the family’s request to have him buried at the Homestead’s El Campo Santo Cemetery and he was interred instead at the Mission San Gabriel Cemetery. In 2002, his granddaughter, Josette Temple, who passed away last October, arranged for his reinterment at El Campo Santo, seven decades after he lost the ranch.