by Paul R. Spitzzeri

On this St. Patrick’s Day, we highlight, from the Homestead’s holdings, a pocket diary kept for a month by Irish-born Andrew Aloysius Boyle, who was traveling from New Orleans to San Francisco to start a new chapter in his life. Born in 1818, Boyle came to the United States as a teenager with his siblings looking for their father, who went to America after his wife’s death and intended to establish himself and send for his children. When that didn’t happen, the offspring went in 1832 in search for their father, but never found him.

After a couple of years working as a lithograph colorist in New York, Boyle with some of his siblings joined an Irish colony in Texas, then a department of México, and, not surprisingly, the community, situated on the Nueces River between San Antonio and Corpus Christi, was known as San Patricio. When Americans revolted against Mexican rule in Texas, Boyle joined their cause and the 17-year old was with a unit at Goliad that surrendered and then was executed, excepting young Boyle, because a brother and sister housed a Mexican Army officer at San Patricio and asked him, if possible, to protect their brother.

His life spared in such remarkable fashion, Boyle soon decamped to New Orleans, where he engaged as a merchant and went on frequent trading expeditions to México. In early 1846, he married Elizabeth Christie, who was born in British Guyana, and the two had a son, John, who died as a toddler, and daughter Maria (Mah-rye-ah). In fall 1849, Boyle was taking a large sum of money to the eastern United States, but the small craft he was taking to get him to a steamship was capsized by the larger craft’s paddlewheel and Boyle lost his money and nearly his life.

When rumor got back to New Orleans that Boyle drowned, his wife contracted brain fever and died, so that when Boyle got home he was confronted with the terrible tragedy. A short time later, he was offered an opportunity to open a wholesale shoe and boot store in San Francisco and Boyle decided to relocate to Gold Rush California. Leaving his three-year old daughter with his wife’s sister, Boyle embarked on his journey, which is largely documented through his journal.

It is said “largely,” because Boyle appears to have run out of paper in the leather-bound book while off the coast of Baja California and several days yet to his destination. Still, the document is an interesting one and came as part of a donation that included related artifacts, of which we’ll discuss at the end of this post.

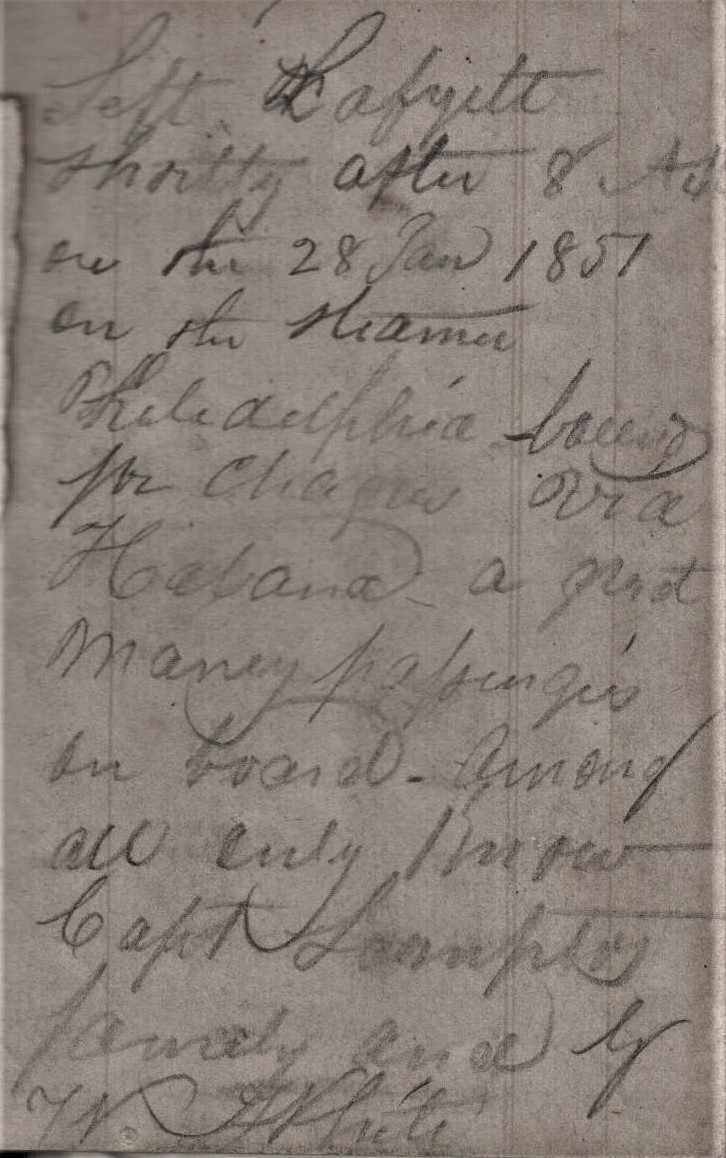

Boyle’s journey began early on the morning of 28 January 1851 as the steamship Philadelphia left Louisiana for Chagres, a port city on the east coast of what is now Panama, but what was then still part of Colombia, that no longer exists by way of Havana Cuba. Boyle recorded in his diary that he only knew a few people, inclduing George W. White, who became his main companion on the trip. He did, however, find a woman who drew his attention, saying that “her face is not handsome, but most intelligent,” though he added “[I] can’t get an introduction.”

As was often the case, seasickness was a very common malady on these voyages and, the day after the ship embarked on its voyage, Boyle wrote “all the ladies sick.” Within a few days, the Philadelphia arrived in the capital of the Spanish possession of Cuba, but not without further problems that led him to note “Sea ruff, nearly all the passengers sick.” On 31 January, he noted that “this the anniversary of my marriage” and then “we passed into the harbour, the handsomest I ever saw.” There was some delay in getting permits to disembark, but Boyle wrote that he “drove all round Havana” with a family before returning to the ship. More rough seas, however, prevented their going back aboard, though attempts to find onshore lodgings proved fruitless and, at a late hour, they managed to get on the ship. Boyle, however, found this his friend White was “still on board, the damn fools not allowing him to land.”

The following day. the ship left for the Central American isthmus and Boyle was keen to make it “in the wheelhouse to get a sight of the magnificent harbour” though he professed to “have neither time nor genius to give a description of it.” Later that day, he and White had a drink on deck to celebrate someone’s birthday. Very quickly, these diary entries turned out to reflect the sheer monotony of sea voyages, with Boyle almost compulsively recording the miles traveled, bearings and the direction of winds and there were occasions in which he, White and others bet each other on their bearings and how soon they would arrive at a port. For example, on the 3rd, he recorded “bet with White we don’t be as far South as 16 [degrees latitude] at noon tomorrow and also that we will be at Chagres by 12 Noon on Friday the 7th.”

At times, ships had to stop to take soundings to determine the bottom to avoid disaster on sand banks and this happened east of Nicaragua on the 4th, which was also when Boyle crowed that he “won my bet with White on the Latitude.” He added the following day that “[we] expect to see the Island of Old Providance [sic], this being the Isla de Providencia, a possession of Colombia, though “it has been blowing pretty fresh this morning, so much so that none of the ladies are on deck.” There was also “a great different in the climate, it is quite warm.”

As the ship approached Chagres, Boyle recorded that he, the ship’s captain, White and a man named Dunbar “have made a bet of a Bottle of wine” on when the landing would take place, as well as the latitude. Haze forced the craft to stand in for a period and he added “had we had clear weather [I] would have won my bet with Dunbar.” While waiting, Boyle took the opportunity to write a letter to his wife’s mother and reported showers during the day. As the ship finally approached shore, he recorded “land plainly in sight ahead, this is my first time to see the Coast of Southern America.” The craft, however, stopped short of landing and anchored in the harbor, where “the Captain treated to Champagne, we had quite a sociable dinner.” Gazing at the place, Boyle wrote, “I am agreeably disappointed in the appearance of this place,” and then spent just a couple of hours ashore conducting some kind of business before returning to the ship for the night.

On the 7th, Boyle and White contracted a boat and took a Mrs. Gibbs and her mother on an excursion on the Chagres River and went as far as 23 miles from that town, finding more interest away from it and spending the night at a place he called “Palo Matias” where he and White slept on the boat and the women in a house. The next day, using poles instead of rowing, they met a boatload of Americans and “they gave our Ladies three cheers.” Arrving at a place called San Pablo, the party found “the charge is $2 for a chicken, the cooking is extra” and “the Ladies will have to sleep in hamaks [hammocks] to night.”

This excursion also found Boyle recording that they encountered many “Mango trees, Alligators and a few pranos [piranhas?]”, though he added sentiments expressed by many Anglos in the Americas held by Spain and México:

In my life [I] have not seen a handsomer [place] or anything like as handsome, it is the greatest pity in the world it is not in the hands of an Enterprising people, there are more wild beasts on the bank of this river than I had any ideas of, Tigers, Bears, and Monk[e]ys in any quantity, we had not seen any of them, but can hear from howling all around morning and evening. Nine out of ten natives that I have as yet seen are pure Negros, and in intelligence far behind the Mexicans.

On the 9th, the quartet left early, but not before Boyle noted that, along with the $2 chicken, the woman who housed them, asked $1 for the women to sleep in the hammocks in a shanty and “thinking her charge outrageous, [we] fooled in the change $1.50.” Arriving a couple of hours at Gorgona, the party “arranged with Juan Francisco to take us four across [the isthmus to the Pacific coast],” though Boyle noted that “this is a handsome place and would be a deliteful [sic] one if art did at all assert Nature, [as there are] Plantans [sic], Bananas and Cokos [coconuts?] in abundance all along the River, [and] the Mango tree is a beautiful one.” As they journeyed, one of the women’s horses fell and he gave his to her and the road was just ten feet wide through hilly terrain. Boyle also complimented a Mr. Arnos [Arnaz?] as he noted “never saw so much hospitality as on this rout[e]” as the group was charged a dollar for a slice of ham and bread and a cup of coffee.

Late that night, the four travelers arrived in Panama City “tired and worn out after a ride of about 27 miles over the worse road I ever saw, the Ladies are most completely fatigued so much so they could not ear or drink, but went to bed,” while Boyle and White strolled through the city for an hour or so. Waking early the next day, the quartet ate and took a walk to the harbor, noted the old city “destroyed by Pirates a long time since” and that “the town is walled and built in the same stile [sic] as all Mexican [Latin American?] towns.” Boyle had other details to offer, such as that there were some 4,000 residents, the homes were usually two stories and that “the Ladies were small Panama hats even in the streets.” He visited a cathedral, but found it in disrepair and only ten persons at a mass officiated by “a Negro priest.”

On the 11th, Boyle took another stroll and “went to the Prison and saw the Negro Hans condemned to die on the 15th of this [month], also saw an American named Whitehead in prison for passing counterfeit money and stealing.” After noting that White and he “are going on the same vessel, the Tennessee,” he added “our two ladies are in trouble, not money enough to pay the way, [we’re] bound to see them through, made them arrangements and am obliged to go security for $100 payable in San Francisco.” He somewhat sourly noted, “[I] can’t help it, it won’t do to leave them now.”

On 12 February, Boyle, who was “tired of the town,” so he went to see the steamship’s agents and added that “Miss and Mr. Thompson arrived, one of the Miss Thompson’s and the old man had each to be carried to a litter.” The next day, he returned to the prison and “saw the Negro and white man again,” adding, “I told the Negro the warden would hang him on the 15[th], he offered to bet me $100 to $5 he would not have courage to do it, the fellow seems perfectly content.” Remarkably, Boyle contniued that, when it came to Whitehead, he “promised to bring the white man a knife to enable him to get out . . . although I know he is a dam[n] rascal.” He went on to say that Whitehead was counterfeiting, but that government officials confiscated his machine and were doing the same, so that “there is now Law in this place.”

Speaking of the law, Boyle then told a remarkable story of how White and he “fell in with a fellow who had been discharged [from a ] restaurant for insolence to White, he evidently wanted to quarrel, White [took] out [a] five shooter, the fellow over on the opposite side of the Street and shot at White who returned, neither balls taking effect, the guard was called out and a general alarm created about town.” White was secreted to spend the night to avoid arrest and Boyle returned to his quarters, where he found soldiers searching for his friend.

On 15 February, after having sent a letter back to New Orleans to apprise his family of his readying to leave on the second and last leg of his journey, Boyle and White headed to the harbor and “went on board with the Miss Thompsons” in the mid-afternooon with the Tennessee heading out a little more than an hour later, bound, with some 250 passengers, for a first stop at Acapulco. He stayed up with the young women until midnight and slumbered for seventeen hours, saying he “felt very much the fatigue and exposure of the day previous.”

Boyle did notice, a couple of days later that “among the Women passengers, we have some very loose caracters [sic] from New York” and followed this with the observation that “most of the New York ladies on board are not of the right sort, thought so from the start.” If these were prostitutes, they were, apparently, headed to buttress the supply meeting the demand for such women in boomtown San Francisco. Meanwhile, Boyle retired at 10:30 on the 17th “after having spent quite a sociable evening on deck with the Miss Thompsons.”

The “entense heat” of Panama cooled considerable even as “main all hands [are] sick,” though from what Boyle did not indicate and, on the 19th, he recorded that “nearly all the passengers again well,” so it may have, again, been rough seas.” Once more, Boyle talked about the women from New York, and Boston as well, who “are nothing better than she might be.” After noting the distance from Panama as being about 240 miles and the west coast of Guatemala being 100 miles away, Boyle went to bed early, remarking that, “tomorrow will be the birthday of my poor wife, God be with her and my child.” On the 20th, he continued by confessing “I think I can almost see her as the family would all kiss her on such a day . . . I hope she is happy, happer than I am.”

More heat struck as the steamer churned north and Boyle found himself unsure as to whether they had neared México or not and appears to have a lost a bet with his friend White on that point. He wrote some letters, including one to “Hugh,” who may have been a brother. Boyle found time to note that “our fancy ladies have got a dance in the quarter deck,” though they went back to their quarters by 9:30 on the 21st too affected by their indulgences in the bacchanalia.

As the Tennessee neared Acapulco early on Washington’s Birthday, Boyle reported that the ship put out all manner of flags, including those of England, France, Chile, Mexico and Peru. Landing was made by about 10:30 and Boyle observed that the town “is small, but handsome” and contained perhaps 1,500 residents. He and White went ashore and “went to the church, plain but handsome,” while “the Mexicans seem the same as all others I have seen,” though what that meant went unexplained. Boyle enjoyed a dinner “where champaign [sic] and other wines flowed freely” and took a walk through town with Mrs. Thompson. A letter was sent home and he was told “the ship will go to sea as soon as the moon rises, all the same to me.” The ship left Acapulco at 11:30 p.m. and Boyle remained on deck until 3 a.m., he reporting that a steerage passenger “has died in a fit” and the body was buried at sea.

The hot weather abated by the 24th as the steamer hewed close to the shore and then turned northwestward towards Cabo San Lucas at the southern tip of Baja California. The next day, it was so much cooler that Boyle was compelled to wear a heavy coat during daylight hours. As the ship passed the cape, he observed that San Francisco was about 1,140 miles to the north, while San Diego, expected to be reached by the 1st of March was just under 700 miles distant. Boyle enjoyed dinner with friend White, an unnamed doctor and a Mrs. Duncan.

The Tennessee remained about twenty miles from shore as it plied its way north and, on the last day of February, Boyle, having enjoued “a stiff brandy and water” before he turned in early the prior night, wrote that it was “one month from home to day near all of which time I have been traveling.” Yet, strong winds arose from north north-west and “nearly all the Ladies [are] sea sick.” He determined, by late afternoon, that they were about 335 miles from San Diego and were in sight of the islands Cedros and San Benito, which the ship was to pass between. As Boyle retired, he noted that the cold winds were still high and the seas rough, so the expected landfall at San Diego was expected to be Sunday the 2nd.

At this point, the diary abruptly ends and the recording of the 18th through 28th was on sheets of loose paper that were pinned together, perhaps indicating that Boyle went through the original pages in the journal and then acquired sheets from another pocket notebook that got him through those last ten days of February. There are fragments of notes, mathematical figurings from his Panama crossing, what appear to be guesses for bets of degrees latitude and miles traveled or distances to ports.

Obviously, it is a shame that Boyle did not get to continue recording observations of the journey, which likely lasted just several more days before the final destination of San Francisco was reached. Included in the donation were a pair of tickets for the Tennessee, one for Boyle and one from “Miss A.E. Thompson” and each covered on the reverses with hash marks for some kind of reckoning for the journey.

A partial piece of paper has seven questions and comments penned probably by someone to Boyle about the length and expenses of the Panama crossing, what baggage and packages to bring, how flags and bunting would sell (in San Francisco?), reminders to write home, and that if Thomas McFadden was found to tell him “all is Right at Home.”

Lastly, there are two short letters, undated, but from several years later, in which Boyle writes his young daughter of bringing her, his mother-in-law and his sister-in-law to California and asking “do you think you will know me?” after so many years apart and she replied thanking her father for the $10 he sent, which used to pay her schoolmaster, and saying “I am so happy to hear that we are all going to California to live” and “I do so long to see you again.”

Boyle, with his wife and in-laws with him by 1856, remained in San Francisco for several years in total and then migrated to Los Angeles, purchasing 22 acres for $4,000 of the Paredon Blanco (White Bluff) across the river on its east side. He continued raising wine grapes long grown there and making wine under that name, lived in an adobe house built by Esteban López, the original grantee of the land, for a couple of years before building a brick house on the edge of the bluff, owned a shoe store, and served on the city’s Common Council.

After his death in early 1871, his daughter and her husband, William H. Workman, nephew of Homestead owners William and Nicolasa Workman, took possession of the property and Workman, with John Lazzarevich, who married into the López family, and banker Isaias W. Hellman, founded Boyle Heights in honor of the Irishman, whose incomlete diary is still an interesting and informative artifact about the sea journey, and Isthmus crossing, to Gold Rush California taken by many thousands during the era.