by Paul R. Spitzzeri

Eddie V. Rickenbacker (1890-1973), the son of Swiss immigrants, was considered one of the finest race car drivers in America when he joined the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) shortly after the United States entered the First World War and became a driver for its commander, General John J. (Black Jack) Pershing, as well as for Colonel Billy Mitchell, who led the A.E.F.’s air combat units.

Under Mitchell’s authority, Rickenbacker trained to be a fighter pilot in the 94th Aero Pursuit Squadron. From April through October 1918, he engaged in missions against the German air forces and piled up 26 air victories, earning a slew of commendations as well as national fame. In many ways, Rickenbacker was the prototypical aviation hero presaging the status afforded to Charles Lindbergh after his trans-Atlantic solo flight in 1927.

In June 1919, Rickenbacker came to Los Angeles for three days of acclaim, characterized as a “celebration and reception,” for his wartime exploits, and tonight’s featured object is an official souvenir compiled under the supervision of a committee that included Los Angeles developer William May Garland (who oversaw the planning and execution of the 1932 Olympic Games in the Angel City,) city council president Bert Farmer, actor Douglas Fairbanks, furniture store owner William A. Barker, and Colonel Anita M. Baldwin (daughter of Elias J. “Lucky” Baldwin and made honorary colonel because of her support of the 160th Infantry Regiment of the 7th Infantry Battalion of the California National Guard.)

Rickenbacker, naturally, was accorded a hero’s welcome as the Los Angeles Express of 21 June reported, “the greeting he received brought a royal flush to the face of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, American ace of aces, when he stepped from the train at the Southern Pacific station today.” The official welcoming committee and a crowds of locals were on hand to lustily cheer for “Rick,” as he was commonly known.

The paper also published a poem by George H. Munson titled “‘Eddie’ Rickenbacker: The American Ace of Aces,” which begins with the snappy verse of

Our “ace,” “Eddie” Rickenbacker,

Greatest swatter, shooer, whacker

And most terrible attacker

Of the pesky German flies—

With his skypodermic gattling

He sent smoky bullets rattling

On the aces and the dueces

Of the kaiser of the skies!

That day’s edition of the Los Angeles Times was typically more colorful than its contemporary, as the paper’s William M. Henry wrote, “Eddie Rickenbacker is in Southern California again after two years spent in accumulating Hun [German] scalps and Allied war medals.” As the war hero “slipped quietly from the overland” train at San Bernardino the day before, he was met by Acting Mayor Farmer and members of the committee and taken to what was still called the Glenwood Inn, better known to us as the Mission Inn, in Riverside for a night. The paper quoted the flying ace as exclaiming,

Gee, but it’s great to be in Southern California again. I’ve been looking forward to this ever since I got home from France, and I’m hoping on my next visit out here to bring my mother along, because this is where we propose to make our home. I’ve always been a booster for Southern California, and I’m going to show I mean it by coming here to live.

Asked if he gave thought to acting, Rickenbacker demurred, stating that he would either go into the car or aviation industries and leave the stage and movies to the experts. He added, though, that he was retiring from auto racing as “he feels he has tempted fate quite enough,” though flying was hardly the safest of endeavors at that stage.

The Los Angeles Record of the same date referred to his prior career in welcoming the hero by observing “when last we saw him he was a popular automobile racer, and 50,000 or more persons thought it well worth while spending a dollar or so to go to any contest in which ‘Rick’ was entered. Today at the Southern Pacific station a whole city struggled to see him and do him honor.”

Among those greeting the aviator at the Central Station, located, naturally, on Central Avenue and 4th Street, was Mayor Frederick T. Woodman and a large cohort of Lodge 99 of the Elks, of whom Rickenbacker was a member. A Record reporter, Eleanor Barnes, penned a piece titled “Rick Saves Girl Reporter From Being Old Maid” recording that “the nearest I ever expected to meet Captain Rickenbacker was to get the picture of him off a cherry flip [this referred to a promotion in which a photo card was offered with a confectionery of that name.]”

She gushed over meeting the ace and having a photo taken with him at San Bernardino and then accompanying him to Riverside. Barnes then wrote that she was advised to ask Rickenbacker how he liked the girls in France and got the reply that he’d returned single, indicative of his like of American women. The reporter noted that she’d always wanted to interview a president, but she “never, ever expected to sit next to the biggest American war hero,” much less have a photo with him published in a paper, albeit her own.

The grand parade included the usual procession of mounted police officers, several bands, grand marshals and aides, government officials, members of the military, fraternal orders and civic organizations. There was a Hollywood touch, courtesy of the mounted cowboys led by Western film star Tom Mix, but given extra attention was a float with a floral reproduction of a biplane used by Rickenbacker paid for by Colonel Baldwin and which took weeks to bring together through the efforts of Henry Siebrecht’s House of Flowers in Pasadena.

The guest of honor rode in Baldwin’s vehicle as it proceeded through a lengthy route downtown (down Central to Fifth, then to Spring north to First, west to Broadway and then south, past city hall, to Eighth Street, where the reviewing stand was located across from the Morosco Theatre) and along with the Times estimated there were some 200,000 persons lining the streets to see the war ace. As the caravan crawled down Broadway, where the crowds were largest, an air show took place overhead. Passing the Broadway department store, the hero was greeted by songs from a 300- strong employee chorus.

Once Rickenbacker was delivered to the stand and crowds pressed in tight around him, a floral bouquet was delivered in a basket, within which was nestled the 9-year old film star Virginia Lee Corbin. After the parade was finished, the aviator was whisked off to the Los Angeles Athletic Club for a informal luncheon, after which he went to Washington Park (formerly Washington Gardens, Chutes Park and Luna Park) where he attended a Pacific Coast League baseball game between the Vernon Tigers and the Seattle Indians and where committee member Barker presented him a silver loving cup.

The following day, Rickenbacker’s fellow Elks threw him a barbecue at the ranch, formerly Rancho Providencia once owned by Workman and Temple family friend David W. Alexander, of real estate mogul William I. Hollingsworth just east of Universal City in the southeastern corner of the San Fernando Valley. The Elks had functions there for at least a few years prior, though the 500-acre property was leased for filming, first with Universal from 1912-1914, then Lasky (Paramount) from 1918-1927 and, finally, Warner Brothers from 1929. In the late Forties most of the ranch was sold to Forest Lawn Memorial Park, which built its second cemetery on the site.

An unexpected addition to the Elks event, however, erupted when an automobile back-fired over dry brush and set off a wildfire. As the blaze spread, a car owned by a staffer in the city’s engineering office was destroyed and two badly damaged and Elks and other guests hurried to save their jalopies or, including Rickenbacker, help put out the conflagration. Once the fire was extinguished, everyone returned to the barbecue, at which the honored guest was given a life membership to the club and enjoyed stunts by cowboys from the Lasky Studio and other activities.

After a visit to the National Soldiers’ Home in what was then called Sawtelle, but which became Westwood, the hero was, on evening of the 23rd, taken to the first Shrine Auditorium, built in 1906 at Figueroa and Jefferson and which burned in a half-hour just six months later in January 1920. There the famed flyer was feted at what was called a reception, though it was much more, especially because of the conspicuous presence of members of the Hollywood film community.

Among the elements of the lengthy program was a patriotic overture and a specially composed march, “Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker” by an orchestra; a song, “Wings of Liberty” from its composer, Dixie Wadlington Matthie; a comedy sketch by Ben Turpin, famous for his cross-eyed visage, and Charles Lynn, a Mack Sennett team; a speech by former boxing champion James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett; a song called “The American Ace;” a sketch by the husband-and-wife actors Carter DeHaven and Flora Parker DeHaven (their daughter was the film star Gloria DeHaven); and other songs, sketches and a poem, “When ‘Rick’ Comes Home.”

After the performances, Mayor Woodman presented the guest of honor with a diamond ring, the four sides of which were flanked (no kidding) by the four Ace cards in a deck, the city logo, and other adornments. The following day, before Rickenbacker headed north to San Francisco for more adultation, another luncheon was held at the Los Angeles Athletic Club in his honor by the Los Angeles Motor Car Dealers Association, which, of course, knew him well from his car racing days.

The souvenir publication offered its own poem, “To ‘Rick'” by J.C. Burton, which lionized Rickenbacker thusly:

Now Rick comes home

From skies that droned with death—

Machine gun riddled skies

That made life but a breath

To draw . . . . and then expire;

Where Utmost Peril found his heart’s desire:

Now Rick comes home

With skill that knows no peer,

With heart by daring steeled,

Rick kept his faith with those

That sleep in Flanders field.

Their torch he bore aloft,

He snatched it where they lay;

Proud were the buzzards of the Hun

That fell to earth this eagle’s prey.

Now Rick comes home, a hero born of War,

To live while there are eyes to scan

On history’s page his name:

But Rick is something more—

A modest, four-square man,

Full worthy of his fame . . . .

So Rick comes home.

The item also has photos of Pershing, other major American military officials and President Woordow Wilson; four kinds of planes used in battle by A.E.F. pilots with descriptions of each craft; and pages with material for the parade, Elks’ barbecue, and Shrine Auditorium reception.

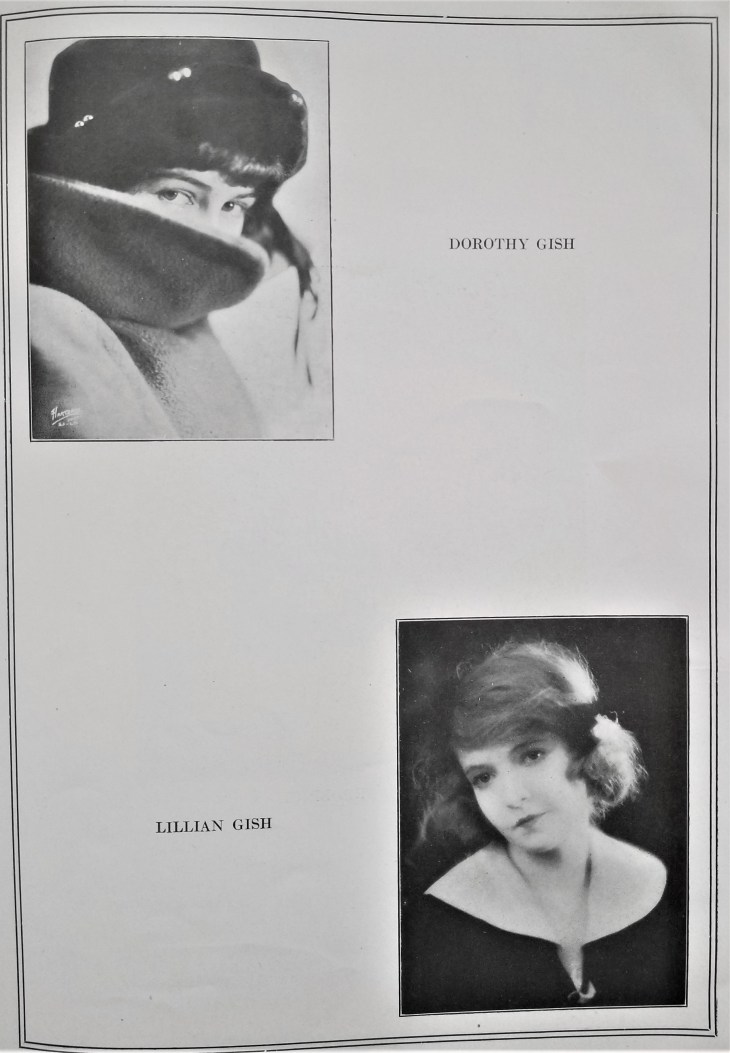

At the end of the document is a photo gallery under the heading of “Aces of Filmland” who were praised by the Rickenbacker Day Executive Committee because they were those “whose splendid cooperation, deeply appreciated, made this souvenir possible.”

Among those featured were actors mostly long forgotten such as Anita Stewart; William Farnum; Marguerite Clark; Pauline Frederick; Charles Ray; Mitchell Lewis; “Smiling Bill” Parsons; William Duncan; Joe Rock; Earl Mongomery; Hampton Del Ruth; Doris May; and Douglas Maclean.

Those who tend to be better remembered are Fairbanks, simply denoted as “Doug;” Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (whose name, though, was left out); the Gish sisters, Dorothy and Lillian; Mabel Normand (best known as Charlie Chaplin’s leading lady for several years); William S. Hart; H.B. Warner (later the star playing Christ in The King of Kings); and film studio executives and owners Thomas H. Ince, Mack Sennett, and D.W. Griffith, who, it was noted, was “By Appointment of the Allied Governments” the “Motion Picture Historian of the War.”

Most surprising of those in the portrait gallery was Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa, who, despite intense anti-Asian sentiment and discrimination (such as California’s 1913 law banning ownership of land by Asians), was a major film star and “forbidden love” heart-throb for white American women in films from the mid-1910s through early 1920s. Hayakawa, increasingly uncomfortable in these roles which did not represent Japanese men, left the film industry three years later to concentrate on stage and film work in Europe and Japan.

He returned to American film after World War II, including in The Bridge on the River Kwai, for which he was nominated for a Golden Globe and an Oscar, though he did not win either. Hayakawa occasionally continued acting in film and television before retiring in 1966 and then becoming an ordained Zen Buddhist master and an acting coach prior to his death in Tokyo in 1973 at age 87.

As for Rickenbacker, he did turn to the automobile industry, trying his own make and then working for Cadillac, as well as serving as the president of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for many years. In the early Great Depression era, he transitioned to aviation and was associated with American Airways and North American Aviation before joining Eastern Airlines in 1935. A few years later, he became the company’s leader, a positioned he maintained for over two decades, followed by a few years as chair of the company board of directors.

Survivor of a deadly Eastern Air plane crash near Atlanta in early 1941 and another crash while serving as a non-military observer that forced him to survive, with the crew, for 22 days at sea, with just one of the eight dying during the ordeal, Rickenbacker, who could be difficult and stubborn, but also fair and honest, died in 1973 at age 82. Nearly a half century later, his is a largely unfamiliar name, though he was American’s aviation hero during and for years after the First World War.