by Paul R. Spitzzeri

Tonight’s presentation for the Chino Hills Historical Society was rescheduled from February, when it was to be given as part of Black History Month, due to the surge of the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus, and it concerned the remarkable story of Lemuel Paul Grant and his ambitious plans in 1949 to remake the Los Serranos Country Club into the Valparaiso Recreation Center. Grant, however, had quite a history leading up to this project going back to early 20th century greater Los Angeles.

He was born Lemuel Pratt Grant in October 1893 in Edgewood, then an independent town and now a neighborhood of eastern Atlanta to Eugenia Flora Sindorf and Frederick Douglass Grant, a brick mason, and was the second oldest of six children, five of which were boys. It is not known why the Grants chose to migrate to Los Angeles, but there was a significant increase in the Angel City’s African-American population during the era. The Grants settled in what is now Koreatown, just north of the intersection of Normandie Avenue and Olympic Boulevard, where the Seoul International Park is located.

In the 1910 census, the 16-year old was listed as a brick-maker apprentice, almost certainly working for his father alongside a brother, Fred, Jr., in that trade. Grant’s first known appearance in the local press, however, was through the result of a fight with a classmate reported on earlier that year in the Los Angeles Times. Notably, the piece began with:

Bluffing with a rifle to show that he was no coward, Howard Grannis . . . was set upon yesterday by Lemuel Grant, a young negro, with whom he had been fighting. In the scuffle, the arm was discharged. The bullet . . . took a downward course, struck a rock and “splashed.”

One young man was mortally wounded and died two days later, while a second was hit with shrapnel. A follow-up story in the Los Angeles Herald found that Grannis’ claim that he laid the gun down after saying he would not shoot a negro and that Grant then attacked him was countered by Grant, and corroborated by another witness, that Grannis shot at Grant and missed, hitting the rock and causing the fatal injury to the young bystander, who was behind Grant.

He was said to be the aggressor in the conflict with Grannis, but this was not Grant’s last time in conflict. For a few years, after he married Anita McClanahan in 1913, with whom he had a son, Douglas, he was a hog farmer near Bakersfield. Grant, however, was arrested in early May 1919 on a grand larceny charge in the theft of a car belonging to William H. “Billie” Carr, who was a screenwriter and director for the Universal Film Company (among its roster of stars earlier in the decade was “Princess Mona Darkfeather,” a.k.a., Josephine M. Workman, granddaughter of Homestead founders William Workman and Nicolasa Urioste.)

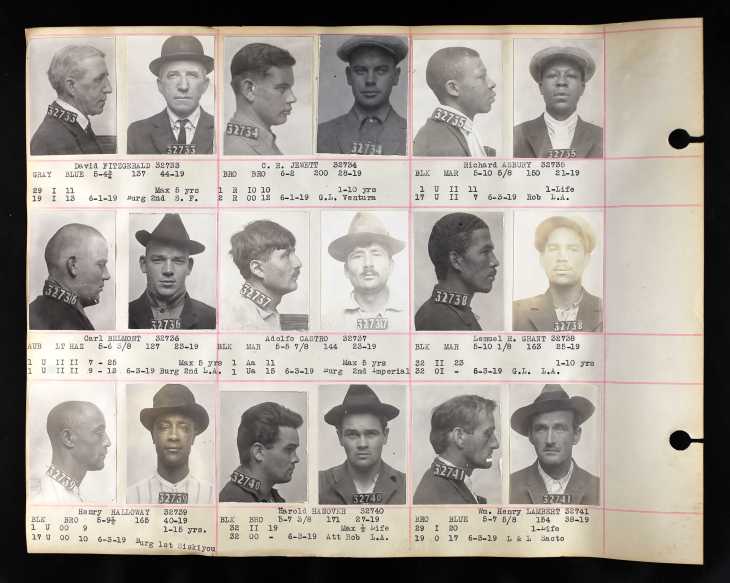

Within just a couple of weeks, Grant was sentenced to 1-10 years, a standard range for the time with parole possible early based on behavior, at San Quentin State Prison. The 25-year old bricklayer was received at the notorious facility on 3 June and it appears he served not much more than the minimum (Grant was recorded at the prison in the 1920 federal census) as he was back in Los Angeles in 1921 and living with his mother and siblings while resuming his occupation as a mason.

Having paid his debt to society and turned his life around, Grant, who changed his middle name to Paul, became a tile contractor and moved to a house just west of Exposition Park, including its newly finished Coliseum, by 1924. Moreover, that year found him, his wife Anita and five-year old son Douglas, taking out passports for the purpose of traveling to South America.

Why is not known, but the family intended, in its application, to see eight countries including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia Ecuador, the Guianas, Peru and Venezuela and it does seem remarkable that an African-American family would take such an extended trip if not for immigration and how common could that have been? It is also not known if there was any move to that part of the world, though there was reference in the Black-owned California Eagle in 1926 that the Grants spent three months in South America.

In any case, it appears that Grant did well with his brick and tile business during the massive real estate boom that hit greater Los Angeles in the early Twenties after his release from prison. Anita hosted meetings of a sorority of Black women at the family’s home and the couple spent time at Eureka Villa, the African-American resort at what has mainly been known as Val Verde, west of Santa Clarita.

During the Roaring Twenties, Grant also soon became known among the African-American community for his impressive command of the golf course. In 1928, for example, the Eagle reported that Grant was partners with Oscar Clisby, widely known as the finest African-American golfer in the region, in a tournament at the Parkridge Country Club in Corona, a facility that opened three years earlier, but, after financial problems ensued, three Black businessmen from Los Angeles began proceedings to purchase it.

After KKK members burned a cross on the front lawn and a lawsuit was filed by white members of the club, the sale fell through—this situation almost certainly had an impact on Grant’s later project. In 1930, Grant was considered a front-runner in a tournament held by the United Golf Association, formed in 1925 for black players to have their own tour.

Within a short time, however, Grant’s marriage ended in divorce and he remarried. He, his wife Dolores and their young son Paul packed up and left Los Angeles in 1931 for South America, settling in Peru’s capital city of Lima, where they remained for a good portion of the Great Depression years. In 1935, a daughter Edna was born there and the family, with Grant continuing his vocation as a tile contractor, resided on Calle Washington (there is a Calle Lincoln, as well) in the Callao section of the capital on the Pacific coast.

By 1938, the Grants were back in the Los Angeles area and soon settled in San Gabriel, where he operated his brick and tile enterprise, while also continuing his avid interest in golf, including playing at a Griffith Park with Clisby and others in a UGA-sponsored tournament. As the Great Depression years were followed by World War II, Grant and Clisby eventually returned to the idea that did not find fruition at Parkridge and came up with a new concept that they hoped would be more accepted and viable two decades later.

In June 1949, it was reported in the Chino Champion (which is still being published after 135 years) that Grant and a syndicate, with such prominent names as athlete and future actor Woody Strode, actor Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, and boxing champion Joe Louis said to be members, agreed to buy the Los Serranos Country Club south of the city from its owners Ken and Consuelo Rogers, with Los Angeles realtor Clara Bartlett Blum, who did business in areas of the city increasingly populated by African-Americans, involved in the deal.

Los Serranos was established a quarter-century before by Long Beach capitalists, who built the 18-hole course around an 1870s adobe house once part of the operations of the Rancho Santa Ana del Chino and opened the facility in 1925. Not unlike Parkridge, the original owners sold Los Serranos within a short time and it had an array of owners over the next 25 years. It was recently known as the Pomona Valley Country Club before Chino automobile dealer James M. Fisher sold to the Rogerses and Blum.

Notably, the paper reported that a group called the “Los Serranos Business Club” quickly formed to contest the sale, though a later report insisted that race had nothing to do with the organization’s motivations. Instead, it was claimed, members were mostly owners of property in a residential tract developed in hand with the country club who were concerned about the effects of water rights and other matters, though the Champion observed that “rumors have been running rife . . . and attempts to sift them into facts have been difficult.”

In any case, Grant and his associates moved quickly to establish the Valparaiso (which translates to Paradise Valley) Recreation Club, which was heralded as a Black-owned enterprise that was also interracial in that anyone was welcome to become a member and enjoy the 320-acre property and its many amenities beyond golf, such as equestrian facilities, clubhouse events, hiking in the nearby hills (where Chino Hills State Park is today), the swimming pool and much else.

A late April 1949 article in the Black-owned Los Angeles newspaper, the California Eagle, indicated that Valparaiso was a “trend-setting example of community planning” and a “unique opportunity of leading the rest of the country in a ‘first’ collective enterprise.” Grant was hailed for seeking to bring the fruition his “lifelong dream” of a “complete recreation center” and as “a man of integrity and conservative tastes. The paper added:

We see in this a fine example of our own people of means exerting their influence and some of their funds to the welfare of the community . . . This project is the result of years of observing and studying the operation of a similar plan in Chili [Chile] and Brazil, where the poorest of people through collective effort made this work. How much better able will we be to put this over?

While it was not specified what Grant saw in South America that inspired him with Valparaiso, he and his compatriots moved quickly to realize their vision, including an Independence Day open house of sorts that reportedly attracted some 3,000 visitors, with the claim that 10% of the visitors signed up for a membership.

An advertisement in the Eagle from late June called the project “the most sensational inter-racial project ever undertaken by our community” and, reiterating the collective element Grant noticed in his South American residency, the center was “not one man’s job nor one man’s honor,” but required “the teamwork, the know-how and the positive action of 3000 people of all races” to meet the membership quota and ensure the club’s survival. Using an entertainment metaphor, it was dramatically stated that “the stage has already been set, the cue has been given, the critics are in their seats, [and] the nation audience awaits your performance in this drama of ‘People Succeeding.'”

By early October, it was announced that Los Serranos was to close on the 9th for a special Valparaiso picnic, but that prospective members could return a week later to inspect the property. The Eagle noted that the facility was “a real show place . . . as many have gone out Sundays to look it over prior to joining . . . [a club] for the use of families of modest means.” Clisby was credited as the one who alerted Grant to the site and who put up $1,000 as the first payment.

While a five-acre camp and picnic ground was also announced, followed by the First Annual Pre-Thanksgiving Fiesta set for 19 November, which included a ladies’ division said have as an entrant Thelma Cowans, a pioneering African-American woman golfer on the UGA circuit who won national titles in 1947 and 1949, the project abruptly came to an end, though in different circumstances from Parkridge, with no explanation found in media searches.

It may have been that the membership quota was beyond reach, though there proved to be problems with water supply at the club and its adjoining residential tract that led to Clara Blum Bartlett, who took control of Los Serranos by the end of 1949, being fined by the California Public Utilities Commission over the matter. Within four years, the club was sold and then leased to a trio including world tennis champion Jack Kramer, whose family still owns Los Serranos today.

As for Grant, he continued with his tile and brick contracting business at San Gabriel and then retired to the High Desert city of Barstow, where he died in 1973 at the age of 80. While Valparaiso was not a success, Grant deserves remembrance for turning his life around in the 1920s, building a successful business, becoming a top-notch amateur golfer, and, after years spent in South America, seeking to realize his dream, unfulfilled as it was.

Thank you!