by Paul R. Spitzzeri

The slow decline of the financial fortunes of the Temple family during the last half of the 1920s, occurring as oil production at their Montebello-area lease with Standard Oil Company (California) dropped precipitously, while spending continued to rise with the completion of their house La Casa Nueva at the Homestead, the opening of the Edison Building in Alhambra and efforts to hit a big oil strike at Ventura, came to a dramatic denouement in spring 1930.

It was then that Walter P. Temple decided, in a last-ditch effort to save the Homestead, to lease the ranch to the Golden State Military Academy, which moved from Redondo Beach and move to Ensenada in Baja California, México to save on expenses and hope that something of a monetary miracle would take place that would allow him to retain the property.

As for his four children, daughter Agnes had just returned to California from a six-month honeymoon and visit in Spain with relatives of her husband, Luis Fatjo, and then settled with him in a substantial house in San Francisco. Younger sons Walter P., Jr. and Edgar were in their second semester at the University of Santa Clara, where their brother Thomas, eldest of the quartet, received his bachelor’s degree in 1926 before moving on to Harvard University’s law school to earn his juris doctorate degree three years later.

Despite his educational pedigree, however, Thomas had no interest in pursuing the law, though he talked about taking the California bar exam. Instead, he became passionate about early California history and genealogy, though he was very much thinking about another career as he wrote a letter to his father from the Hotel Plaza in San Francisco on 4 May 1930 that is remarkable for its content at the time the Temples vacated the Homestead.

Addressing his father by the usual “Dadup,” the 25-year old began by writing,

[I] will try & give you some idea of what has happened since you left [for Ensenada.] The things I felt that I didn’t need up here I put at Tia Maggie’s and stored the rest in the warehouse, mostly Agnes’ things.

The day I left I saw Joe Mullender & had a long talk with him, the most we can get for the property is 2000 an acre, that is all that he is asking for his property & I don’t think he’ll ever get it in cash, so the best we can do is to trade it for income property.

Rosebud, I did not see as she was away when I called but left a note. I felt rather sad of course leaving the Puente behind, but I feel much better now, as no doubt you do too—being away from it all.

Walter, Sr. left the Homestead in April to make his move to Baja California and Thomas talked about storing personal possessions at the house of his father’s sister, Margarita Temple Rowland, who remained in the modest dwelling built for her by her brother at the west end of the Homestead along Turnbull Canyon Road. The warehouse was an adobe building along Evergreen Lane, which went from Turnbull Canyon to El Campo Santo Cemetery, and which was attached to a small house occupied by ranch foreman Frank Romero and his family.

Thomas referred to Joseph and Rosebud Mullender, family friends whose ranch was north of Puente and Rosebud was a granddaughter of Elias J. “Lucky” Baldwin, who took possession of over 18,000 acres of William Workman’s half of Rancho La Puente after foreclosing, in 1879, on the loan he made to the failed Temple and Workman bank. Despite that history, the Mullenders became friendly with the Temples and Thomas hoped to get some insight on what might be possible in selling the Homestead or trading it for income-producing properties. The problem was that the ranch couldn’t be sold because it was encumbered with indebtedness to California Bank, so the idea raised by Thomas in his missive just was not realistic.

He continued his correspondence by informing his father that he and Milton Kauffman, Walter, Sr.’s business manager, then went to “the Lease adobe,” this being the Basye Adobe, built in 1869 and acquired by the Temples in 1912 and used by them as their house until the drilling of oil took place five years later. Thomas added that he “saw Manzanares,” this being Victor, whose family settled in the community known as Misión Vieja, or Old Mission, in the mid 19th-century. Manzanares, who died four months later, resided in a house directly across San Gabriel Boulevard from the Basye Adobe and a recent post here discussed a donation from descendant Bernard Manzanares showing the family’s house.

From there Kauffman and Thomas drove north through heavy rain to San Luis Obispo and stayed in the Anderson Hotel, which still exists as a residential complex. The next day, with the weather clear, the duo headed north and go to Salinas, where they sought to visit with a man whose brother was an advisor to Agnes Temple’s husband Luis, a former Santa Clara classmate and roommate of Thomas, and found he was away. On arrival at San Jose, Thomas hoped to see someone he knew from his Santa Clara years, but this person was also unavailable. He was able to leave books and “impedimenta,” which apparently meant material that was not immediately needed, the Roca family, who he met through Luis Fatjo and who became close to the Temples.

Having conveyed to his father that people sent their greetings and asked Walter, Sr.’s health, Thomas stopped at the University of Santa Clara and talked to William Gianera, a priest and prefect who became the institution’s president in 1945, “and explained to him the circumstances” adding that “he lent me a willing ear and has since had a nice chat with Walter Jr. so don’t worry about him.” This last comment likely had to do with the academic struggles of Thomas’ brother.

Thomas then spoke to then-President Father Cornelius McCoy, who “was very solicitous about our future & he was kind enough to address a personal letter” introducing him and Kauffman to Santa Clara alumnus and head of its alumni association William J. Kieferdorf, who ran the trust department for the Bank of Italy, which in November changed its name to the Bank of America, now a financial behemoth in this country.

From there, Kauffman and Thomas drove to San Francisco where Agnes and Luis lived and Thomas told his father “I felt very happy to be united again to my dear sister and her in-laws.” The following day, they arrived at the headquarters of the Bank of Italy and, while Kieferdorf was out of town, Joseph Cereghino, an assistant vice-president received them and “we had a fine talk . . . and I met the head of the Personnel dept.”

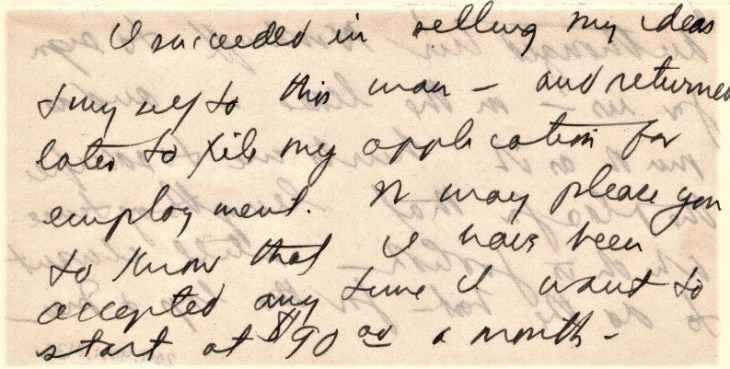

This led to the fact that Thomas “succeeded in selling my ideas & myself to this man, and returned later to file my application for employment.” He added, “it may please you to know that I have been accepted any time I want to start at $90.00 a month.” With this news, he went on that “I am starting from the Bottom at the adding machines, but I am landing in a few months in the Trust Dept. at $150 per month” and told his father “I feel that I have been very fortunate & as soon as I get well settled here I am going to buckle down to hard work & make you proud of me.”

Walter, Sr.’s attorney George H. Woodruff was in San Francisco and he, Kauffman and Thomas “had a fine meeting here,” though Thomas “wished you could have been here just watching us.” The news was conveyed that “we have authorized Mr. Woodruff to sign for us—on the lease—and as much as it hurts me to sacrifice the place for that length of time which is foolish, still I want to do the best for the boys & Ines [Agnes].” This referred to the Montebello lease, though it is not yet known specifically what the arrangement entailed.

After this piece of business, Thomas noted that his brothers were doing well and would soon finish their year at Santa Clara, adding “Walter wants very much to get a job at the Military School” when it opened the 1930-1931 school year at the Homestead. He continued, “I hope you got down to Ensenada without much difficulty,” though he wondered what his father was going to do with all the possessions he carted down there and said “you must known what you are doing, and we won’t say a thing.”

Thomas then turned reflective, telling Walter, Sr.:

I feel that what has happened, is for the best and we must have in God & feel confident that if we only ask him, if we only humble ourselves and forget material Goods for they are very transitory, if we but forget for futile the efforts of man are to solve things and place our faith & our destiny with Him, that we cannot go wrong.

We all want you to think about Him, when you are down there. We are all praying for you, never forget that. Placing saints & images around you is of no avail if you have no faith in them. They make you just a hypocrite, for in order to get the best out of anything, you must believe, you must have faith.

As he concluded, Thomas added, “I am very happy here and I know I shall make a go of it,” except to say “we miss you all as much as ever, and the Puente, but time will tell and let us hope & pray that all is for the best.”

Whatever his intentions regarding a career in banking, Thomas did not either take the job or stay at it long. A Ventura newspaper from late July noted that he was a resident of San Francisco when he and his sister ventured down from the Bay Area and joined their brother Edgar in visiting their cousin, Dr. Charles P. Temple, Jr., a local dentist.

By the end of August, however, it was recorded by the Los Angeles Times that Thomas was recently recruited to assist in the planning of the early September fiesta celebrating the birthday of Los Angeles. When there was a claim by the Reverend Zephyrin Englehardt, a historian of the California missions, that the Angel City was founded in December because of a late 18th century document that stated it was established at the end of 1781, Thomas decided to seek out an early record at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and found another researcher, Lindley Bynum of the Huntington Library, was there for the same purpose. The pair then found a manuscript that stated that Los Angeles was founded on 4 September 1781 and this date became official, starting with the 150th anniversary fiesta in September 1931.

This letter, donated to the Homestead five years ago by Thomas’ niece, Ruth Ann Temple Michaelis, is remarkable for its information about the family’s move from the Homestead, Thomas’ plans after the migration, and his feelings about this dramatic change in their fortunes.