by Paul R. Spitzzeri

It was one of those seemingly improbable stories of a young man arriving in Los Angeles with little money, no concrete prospects, but with enough initiative and drive that he embarked on what is almost the prototypical “rags to riches” story, but the tale of John G. Bullock was a remarkable one, which led to his running one of the most successful department stores in the Angel City.

Born in 1871 in Paris, Ontario, Canada, southwest of Toronto, Bullock came from a family of very modest means and left school at age 11 to earn $2 a week as a grocery store clerk and help support his widowed mother. Finding mercantile work to his liking, he found employment at Rheder’s, where he stayed until 1896. Having heard of California from a pair of uncles engaged in mining there, Bullock was given $150 and plenty of home-cooked food from his mother and migrated to Los Angeles.

He arrived in late January, but found that economic conditions, because of a national depression that burst forth in 1893 and lasted about four years, were such that he could not readily find work. He scoured the newspapers each day and saw that goods from a bankrupt store owned by J.A. Williams and Company and called The Broadway were being sold by the assignee, Arthur Letts, a native of England who lived in Toronto and then worked in dry goods in Seattle before coming to the Angel City and purchasing the bankrupt business and holding the sale.

Bullock related that he initially turned away by Letts, who said he had all the workers he needed, but he persisted as he saw enormous crowds enter the store’s front door and exit through the rear. He made his way to the back and was recognized by Letts, who asked him if he wanted work after all. He was offered $2 per day and put behind the domestics counter and, within a few days, wandered to the men’s furnishings (accessories) department. Bullock worked long hours and decided to try his hand as a delivery driver at a bakery, but found that not to his liking.

Though he had an offer at another store, Bullock went back to The Broadway, where Letts offered him a little less of a weekly salary, but indicated he hoped to pay him $75 a month if he would return. After initially demurring and claiming later that he wasn’t even sure why he went back, Bullock rejoined the enterprise. He worked his way up to being a buyer and finally store manager as The Broadway was remade into a top mercantile business by the hard-working and enterprising Letts.

A biographer of Letts wrote that Bullock possessed “the makings of a fine executive” including character and that “he was just, truthful, temperate, benevolent, magnanimous and sympathetic” as well as “direct and straightforward with every man [and woman?].” With what would seem to be the qualities of a nearly perfect human being (at least in a fawning biography of a man who had just about those same attributes!), Bullock was then chosen by Letts to open a new store in a building erected by Edwin T. Earl at Broadway and Seventh Street and given full power to buy the stock and hire the employees.

On 2 March 1907, Bullock’s opened and, despite the next big depression erupting that fall, the business prospered. After five years, the 7-story store was augmented by a 10-story building, with a sub-basement and full basement, adjacent to it, nearly doubling the floor space. In 1917, the former Pease Furniture Company building on Hill near Seventh was added and, two years after that, the northeast corner of Hill and Seventh was acquired—the result was nearly 800,000 acres of floor space, or around 18 acres. The business was incorporated in 1927 and enough funds raised through stock sales that, in late September 1929, the remarkable Art Deco-style Bullock’s Wilshire was opened. By the time Bullock died in September 1933, there were also stores in Westwood Village and Palm Springs.

Bullock was known for his work with the Y.M.C.A., as a trustee at Occidental College, which was a Presbyterian-affiliated school, and with his church in that denomination. Perhaps his best known public service endeavor was active work with the Colorado River Aqueduct, as he chaired a committee that worked toward a successful voter-approved bond issue of $220 million towards the massive water delivery project (which is now very much in the news as climate change has drastically reduced supply from the river and is forcing difficult choices on the federal government and the several states, including California, involved with it.) He was also chair of a bond committee for the Metropolitan Water District, formed to distribute the water from the project.

Bullock was elected twelve times to head the Retail Merchants’ Credit Association of Los Angeles; was on the executive committee for the All-Year Club, which promoted and boosted the region; was vice-chair of the multi-agency Community Chest in 1928; and, just before his death, became a trustee of the California Institute of Technology. As a member of the Angel City elite, Bullock belonged to such organizations as the Los Angeles Country Club, the Los Angeles Athletic Club, the California Club and the Jonathan Club—the latter was the focus of yesterday’s post.

As the city grew with great rapidity, so did Bullock’s, which also took full advantage of the enormous rise in the commercial side of the Christmas holiday. Its advertisements, often full-page ones with notable graphics, promoted its regular stock of goods for women, men and children, as well as the literal “bargain basement” offerings of the subfloors added to the enterprise in 1912. While women were, of course, the main target of these ads, it is interesting to see that the highlighted artifact from the Homestead’s collection for this post, with women as the intended audience, was dedicated “For the Men’s Christmas.”

A short paragraph observed that “AT HOLIDAY TIME more than at any other time men’s thoughts turn to things to wear,” and readers were encouraged to “have what you buy just a little better than he would buy” so that “it will be a ‘Merry Christmas’ that will last for months.” To that end, “this little booklet is gotten up with an idea of helping those women who have gifts to choose for men” and to answer the eternal question, “What in the world will I give him?”

For shirts, it was averred that “no season has ever found us ready with such complete stocks” with material, style, color and pricing that “will all prove pleasant surprises,” including costs from $1 and up. As for pajamas, it was asserted that “there’s not a man but would appreciate a pair these cold nights,” with prices ranging from $2 to 5. Fancy vests and coat sweaters, the latter deemed appropriate “almost everywhere—especially for driving and motoring,” were in the $2.50 to $3.50 category.

Some items, such as socks and handkerchiefs came in gift boxes, while it was determined that “it’s clever now to have the Tie, Socks and Handkerchief to match” in sets priced at $1.50 and $2.00. With respect to handkerchiefs, these were “a gift that is always acceptable to any man” while “no man ever had too many ties.” Meanwhile, Bullock’s offered “Perrin Gloves,” made in Paris since 1893 and still with us today, with these considered “the best gloves in all the world” and ranging from $1.50 to $3.00, including “a big showing of fine gauntlet gloves for motoring and driving.”

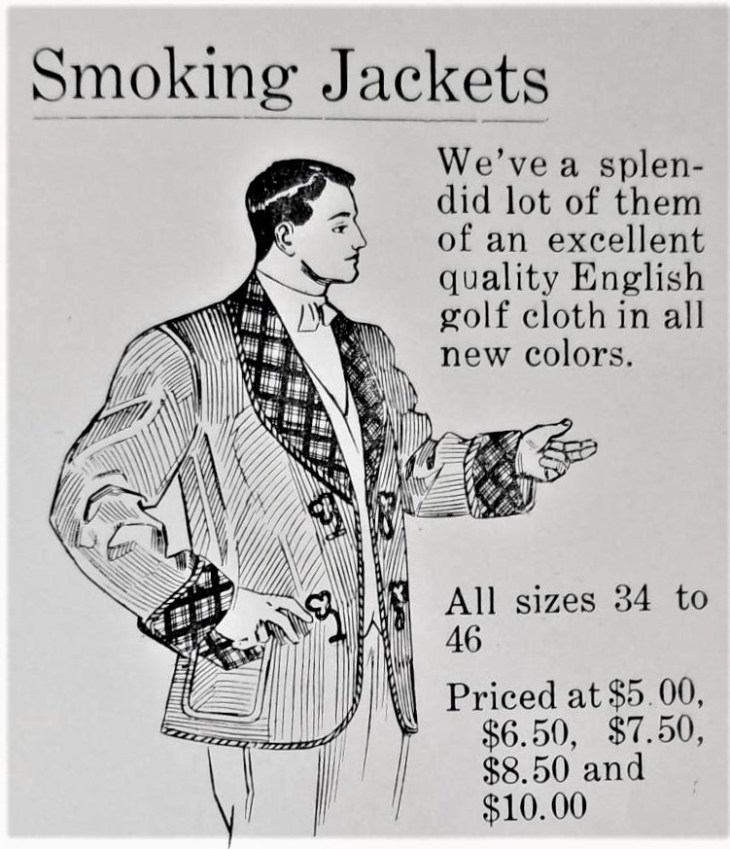

Suspenders included some with matching ties, while mufflers and slippers (“What man wouldn’t like a pair to slip his tired feet into, at evening time?) were other notable accessories. The selection of smoking jackets were “of an excellent quality English golf cloth in all new colors: and were listed from $5.00 to $10.00, while bath robes were guaranteed to be such that “one would be a happy ‘good morning’ for 365 days in the year as well as a ‘Merry Christmas’ on the 25th of December” and fetched from $3.50 to $10.00.

As for “Other Suggestions,” there were, in an age where smoking was far more common than it is now and long before the “Surgeon General’s Warning” was mandated by federal law in 1965, brass smoking sets, silver or gunmetal cigarette cases, and gunmetal safes for matches and sterling silver topped cigar jars. A little silver handled hat or whisk broom was a nice little grooming gift, while Gillette safety razors included “a new pocket style at $5.00—or in [a] leather case with soap and brush at $9.00.”

These certainly weren’t the only men’s furnishing offerings for the store whose founder got an early start in that department at the bankrupt Broadway, but they constituted a good sample of what was available for women seeking the answer to that interminable question of “What in the world will I give him?” Hopefully, everyone has found a suitable answer to that question in general and we wish all of you the best of the holidays, whether it is for Hanukkah, which concludes on Christmas Day, Kwanzaa which runs from the 26th to New Year’s Day, or Christmas.