by Paul R. Spitzzeri

One of the most famous transplants from the Montana copper mining boom to Los Angeles in the late 19th century was William Andrews Clark, the “Copper King” in Butte, who left his mark in many areas of life in the Angel City as well as throughout the western United States. Far less known was Nelson Story (1838-1926), whose mining, cattle, milling and banking interests, some involving controversy over his methods and possible “greasing of palms,” were in Bozeman and who came to Los Angeles, as many wealthy people from elsewhere in the country did, for winters, starting in the early 1890s.

Story quickly began investing in local real estate, but his biggest investments were made in March 1895, when he acquired two downtown properties for $85,000. One was on the west side of Spring Street just north of Seventh Street and the other at the southeast corner of Broadway and Sixth Street. Neither was yet within the expanding commercial district of the Angel City, but would be in fairly short order.

The Broadway and Sixth Street parcel was acquired from James B. Lankershim, owner of much of the southern San Fernando Valley and who built a two-story commercial building on the property, which was given as a gift by Story to the youngest of his three sons, Walter P. (1883-1957), the other two being Nelson, Jr. (who became a prominent figure in Bozeman) and Thomas (who also came to Los Angeles—see below), when he was just a teenager.

In February 1905, it was recorded that Walter deeded back the property to his father for $137,000, while Nelson, in turn, bestowed a life estate on it to his son. A little over a year, however, the younger Story filed a lawsuit against the elder and claimed that the 1905 arrangement, in which the large sum consisted of bonds from Montana, was done without his knowledge, even though both deeds were kept in a safe deposit box at a Los Angeles bank with instructions that they were not to be surrendered without the approval of father and son, and that it conveyed title not to Walter, but to any children—he’d recently been married.

Apparently, the brouhaha was settled out of court as there was no further record of any action reported in the papers and, in 1908, Nelson and Walter embarked together on the construction of what was easily one of the finest commercial buildings in Los Angeles, what became generally known as the “W.P. Story Building.” The Beaux Arts-style structure, at the height limit of 150 feet comprising eleven stories with a basement, was designed by the well-known architectural firm of Morgan and Walls. After demolition of the Lankershim building, excavation work began on the new structure in May.

The Los Angeles Herald of 11 October 1908 reported that $300,000 in contacts was let for the early building stages “and more than 100 men are engaged on the foundations, concrete and steel work” and some attention was paid to the fact that the foundations were to go forty feet below street level and involve reinforced concrete footings and cantilevers with steel rods. The local Llewellyn Iron Works was handling the steel manufacturing, involving some 1.7 million pounds, while the general contractor was originally Carl Leonardt, but who was replaced by Weymouth Crowell.

The 21 February 1909 edition of the Los Angeles Times included a photo of the steel structure as well as an architectural rendering of the finished building and a brief article observed that “rapid work on the magnificent” edifice “is attracting the attention of the thousands of people who pass the great structure daily,” this being testament to the fact that the scope and scale of the project was a reflection of the great advances being made in commercial construction.

Not quite two months later, in its 21 April issue, the Los Angeles Record‘s Katherine M. Zengerle wrote a feature with the headline “Open Dangers Scorned By Steel Men High In Air For Small Pay.” While there might be media reports of injuries or deaths, which were all-too-common on such major building enterprises, this was a rare one on the nature of the work. Zengerle spoke to J.C. Goecks, a structural iron worker, who insisted

Danger? There ain’t no more danger about this work than there is about any other work. People look up and keep thinking what a risk we run and that sort of thing. If we ever stopped to think about it, I guess there wouldn’t be any steel frames . . . I know that if I’d look down I’d be lost, so I don’t do it. That’s about all there is to it.

As to his pay, Goecks told Zengerle he earned all of twenty-five cents per hour or $2.50 a day and he allowed “that ain’t so much if you’re thinking about danger,” but he added he was relatively new to the work and more experienced workers made a dollar more per day “and, of course, the foreman gets more.”

On the other hand, he mused that structural iron workers made more than most laborers and then noted, when it came to the possibility of higher pay somewhere else, “I guess they are where there are unions, but, you see, there isn’t any union here.” Los Angeles was notorious for being a predominantly “open shop,” or non-union, city, but Goecks then offered that “there ain’t so much money in it, but I think the pay is fair.”

Strikingly, when the journalist asked about the legal requirement that a floor be at least four stories below where men were working, Goecks replied, “I believe there is, but they don’t seem to enforce it here” and then opined that “I don’t see how a floor would help much if a man did fall.” As to whether the risk increased at the higher levels of a building, he mused that “if a man can stand it to go higher than the first few stories, he don’t care how high he goes.” Because of the height limit, set to avoid the continual darkness in streets of cities where there were no such prohibitions, the laborer felt that, as “the buildings here ain’t so very high” he didn’t really “see what difference it would make whether I fell from a high story or a lower one.”

In capital letters, the article observed that

UNDER THE EMPLOYERS’ LIABILITY LAW, THE MEN WHO WORK ON STEEL FRAMES ARE GIVEN NO PROTECTION IF AN ACCIDENT OCCURS. SHOULD A MAN BE HURLED TO THE GROUND AND DASHED TO DEATH HIS WIDOW AND CHILDREN WOULD RECEIVE NO FINANCIAL HELP FROM THE FIRM WHICH PROFITS BY THE SERVICES OF THE HUSBAND.

In the meantime, the more liberal Record and Zengerle concluded, “but men and women and children must eat and live, and so these fearless workers do their tasks, day by day, with hardly a thought for the hundreds of persons who pass by below” and Goecks, labeled “the intrepid,” ended his interview by stepping on a beam, swinging his hat and saying good-bye, “and was hauled to the top of the building.”

Three days later, the Los Angeles Express reported that half the 300 offices were leased, eight months before the contemplated completion of the building. and the steel structure, encompassing 2,400 tons of metal, and work was being initiated with masonry, plaster, fire escapes and other elements. A photo showed the steel structure and another depicted the site when the Lankershim building was there a year prior.

Interior woodwork and marble contracts were soon to come, while that for the ornamental iron work was already secured and also mentioned were the boilers and engines to power four passenger and two freight elevators, for lighting, and filtering of water, of which both hot and cold were to be supplied along with compressed air. The cost was then pegged at $700,000, more than a third higher than the original estimate.

The marble contract was signed in May and that for the woodwork in July. In the meantime, the major tenant secured for the ground floor was the well-known clothing company, Mullen and Bluett, the precursor of which opened in 1883 while the firm of that name succeeded it six years later. Walter Story later became the chairman of the board for the company among his many business endeavors in finance, mining and real estate.

By the first of August, the terra cotta coating, with elaborate decorative work a striking feature, was being applied to the brick walls and the effect was noted by the Times as “clothing a steel skeleton.” At the end of the month, reported the Herald, the cladding and walls reached the ninth floor, while the concrete floors and slabs on the roof were finished and the plumbing and heating (by steam) systems were moving along nicely.

A photo in the Express in late September showed all but the tenth floor and penthouse level, where Story and his wife resided, were completed with respect to the exterior, and an early November image in the Herald revealed that the finish to the outside was essentially done. Another highlight came in February 1910 when it was reported that the plate glass windows for Mullen and Bluett were reportedly the largest on the west coast, requiring over a dozen men to install each of the $1,000 sections.

On 10 March, the store finally opened, more than two months behind schedule, and the next day’s Times recorded “Los Angeles has welcomed a very beautiful addition to the list of its expanded business establishments” with the clothier considered “one of the finest exclusive men’s shops in the entire West” and “a perfect example of what can be produced in this city, since every piece of furniture, all of the window decorations, cases and other fixtures were made here.”

Public support of the store was manifested by a great many floral displays shown there, while Hart, Schaffner and Marx, the well-known clothing manufacturer in Chicago, sent a large basket roses and the Mullen and Bluett employees corps contributed a 12-foot high horseshow with red and white carnations. It was reported that there were 50,000 visitors over six hours wandering through the 28,000 square feet on the first floor, including a mezzanine, and basement, though this latter was not fully ready for opening. Arend’s Orchestra provided entertainment and manager Arthur Mullen proudly noted that “our establishment typifies the aggressive business spirit which prevails throughout Los Angeles.”

Tenants of the upper floors included a whole level devoted to dentists with specially outfitted suites for that profession, while oil companies, realtors, building and development firms, architects (including Morgan and Walls) and mining companies were among those occupying other offices. The extensive use of marble in the lobby and a stained glass skylight modeled after the famous works of Tiffany and Company are specifically highlighted by the Los Angeles Conservancy in its webpage devoted to the structure, which is still with us today.

A little more than a decade later, in 1921, Walter and his brother Thomas completed the Los Angeles Stock Exchange Building on the Spring Street property acquired by their father over a quarter-century before. While the exchange moved at the end of the decade to its distinctive quarters across the street and a bit to the north, the structure long housed Barclay’s Bank and is, of course, now comprised of lofts with a café at the ground floor.

In 1923, Story, who was previously married and divorced, married Lorenza Lazzarini, a San Francisco native whose father was from Italy and whose mother was born from German parents and who was an actor with parts in a few films produced by Paramount-Artcraft and some local stagework, as well. The couple soon built, off Laurel Canyon Road in what is now the Fryman Canyon area of Studio City, at the base of the Santa Monica Mountains, a Spanish Colonial Revival house on a 16-acre estate.

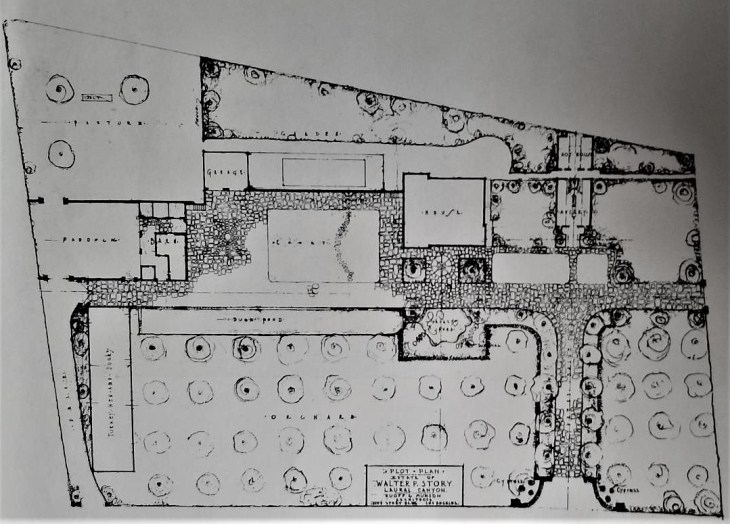

Two pages of a 1925 edition of Architectural Digest, the lavishly illustrated journal published quarterly by John C. Brasfield, are devoted to the newly constructed property, including photos of the house and gateway and garage, while a plot plan is also provided from architects Ruoff and Munson, showing the residence, garage, court, barn, paddock, pasture, duck pond, aviary, fox house, house for turkeys, hens and ducks, and orchards and gardens.

The 23 November 1924 issue of the Times, includes an architectural rendering of the dwelling, now just shy of 10,000 square feet, along with other substantial houses such as the Alhambra French-style chateau of Sylvester Dupuy, business partner of Walter P. Temple with Temple City. The designers were Allen Ruoff (1894-1945) and Arthur C. Munson (1886-1969), whose short partnership of several years largely included residences, along with a smattering of commercial buildings, schools, and libraries.

Walter and Lorenza Story were avid entertainers in the upper echelons of Los Angeles society, while he pursued his career as a California National Guard and United States Army officer, which culminated in his being commissioned a Major General with command of an infantry division just prior to World War II, at which time poor health led to his retirement from active duty. The couple divorced in 1951, after she accused him of mental cruelty, and Walter married a third time not long before his death in 1957, while Lorenza, who lived in a town northwest of México City and in Carlsbad in San Diego County, died a dozen years later.

A previous post here featured a panoramic photo taken from the Story building not long after its completion in 1910 and includes some of his history, so this post looks to avoid too much duplication while giving more of his background, including that of his landmark building, and to a lesser degree, his remarkable estate, of which the house still stands next to the 128-acre Wilacre Park, which features popular hiking trails, a picnic area and other amenities.

Finally, there are many other notable and interesting houses of the well-to-do in the issue of Architectural Digest, which we’ll look to share more of in an upcoming post, so be sure to check that out.